- Home

- Advertise With us

- World News

- Tech

- Entertainment

- Travels & Tours

- Contact US

- About us

- Privacy Policy

Top Insights

Transnational Organized Crime in Mexico: Continuity, Change, and Uncertainty under the Sheinbaum Administration (Part I)

This essay is the first in a three-part project that examines Mexico’s security landscape under President Claudia Sheinbaum. It analyzes the criminal structures and institutional conditions inherited by the current administration, with particular attention to the territorial reach, organizational diversity, and adaptive capacity of organized crime across Mexico. By mapping the current configuration of criminal networks, this installment establishes a baseline for assessing policy choices and reform trajectories. The second essay, to be written following Mexico’s mid-term elections, will examine how evolving political dynamics shape the Sheinbaum administration’s security strategy, including the expanded role of the armed forces, the implementation of judicial reform, and intergovernmental coordination. The third essay, to be completed at the end of Sheinbaum’s administration, will assess the longer-term consequences of these policies for US–Mexico security cooperation, regional stability, and governance in the Western Hemisphere.

The context in which transnational organized crime operates in Mexico is undergoing a profound transformation. The general elections of 2 June 2024 consolidated political power around a single governing coalition led by the Movimiento de Regeneración Nacional (Morena), constituting a critical inflection point in Mexico’s party system and institutional balance. Through a combination of electoral outcomes and strategic legislative agreements, this coalition has secured effective constitutional majorities in Congress, thereby expanding its capacity to pursue far-reaching legal and institutional reforms. Under the leadership of President Claudia Sheinbaum, these developments carry significant implications for the governance of security, the role of the armed forces, the prospects for police reform, and the state’s broader approach to organized crime.

Yet continuity has proven as consequential as change. By the close of the López Obrador administration in 2024, cumulative homicides exceeded 190,000[1]—surpassing the totals recorded under the two preceding governments, and establishing a historically high baseline inherited by the Sheinbaum administration. Despite shifts in political leadership, Mexico continues to rank among the most dangerous countries in the world for journalists, while entrenched impunity, corruption, and weak investigative capacity persist across judicial and law enforcement institutions. The unprecedented violence surrounding the 2023–2024 electoral cycle—the deadliest in Mexico’s modern history—highlighted the deep and enduring penetration of criminal organizations into local governance and political competition. This legacy of violence and institutional fragility poses a clear policy risk for the Sheinbaum administration, as entrenched corruption threatens to blunt the impact of any security or judicial reform.

Today, the principal challenge confronting the Mexican state lies in the sustained and, in many regions, expanding capacity of organized criminal groups to exercise territorial control. This landscape is more complex than narratives focused narrowly on drug trafficking suggest. While the drug trade remains a central pillar of organized crime, a growing share of criminal power is rooted in locally embedded economies that do not depend primarily on transnational flows. Extortion, kidnapping, fuel theft, money laundering, arms trafficking, migrant smuggling, and human trafficking now constitute core revenue streams across multiple regions, often surpassing drug trafficking in their direct economic, political, and social impact on communities. This challenge is further intensified by the renewed Trump agenda, as border hardening and mass deportations are likely to reshape smuggling markets and expand opportunities for criminal control inside Mexico.

Mexico’s illicit markets operate according to distinct organizational logics that respond directly to government policy choices and enforcement practices. Markets tied to cross-border flows—such as drug trafficking and migrant smuggling—depend on transnational networks and are highly sensitive to border enforcement, migration controls, and bilateral security policies. By contrast, locally embedded activities—such as extortion, fuel theft, and kidnapping—are sustained through territorial coercion, political protection, and informal governance arrangements. While criminal organizations often specialize, they increasingly diversify as a rational response to policy pressure: intensified border controls, militarized security strategies, and shifting migration regimes raise the costs of single-market dependence. As a result, criminal groups hedge risk by operating across multiple illicit economies simultaneously—drug trafficking organizations expand into extortion or migrant smuggling, while local predatory groups selectively plug into transnational networks when policy and enforcement conditions create new opportunities. This adaptive diversification explains why single-issue enforcement strategies—focused narrowly on drugs, borders, or migration—consistently fail to reduce overall criminal power and violence.

High-impact violence in Mexico continues to be widely attributed to drug trafficking organizations (DTOs), but this framing increasingly obscures the sources of contemporary insecurity. While the Sinaloa Cartel and the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (Cártel de Jalisco Nueva Generación –CJNG) remain the most powerful criminal coalitions, they operate within a far more fragmented and diversified ecosystem. Other established organizations—including the Gulf Cartel, the Cártel Santa Rosa de Lima, and the Northeastern Cartel (Cártel del Noreste)—coexist with a growing number of splinter factions and semi-autonomous cells that function as enforcers, transporters, or retail-level distributors. Increasingly, however, a significant share of violent confrontations is driven by criminal paramilitary groups and specialized cells focused on extortion, kidnapping, and migrant smuggling—many of which operate primarily in local or regional markets and have limited direct involvement in drug trafficking or transnational criminal activity.

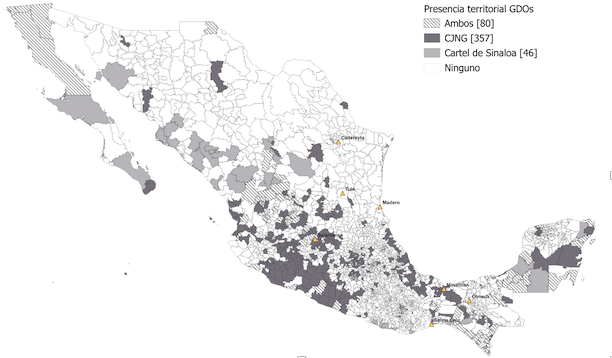

Recent assessments by Lantia Intelligence, a leading Mexican security consultancy, indicate that organized crime in Mexico continues to be structured around two dominant criminal coalitions—often described as “criminal corporations”: the Sinaloa Cartel and the CJNG (see Map 1).[2] These organizations sustain expansive networks of associates and collaborators, which Drug Enforcement Administration sources estimate to comprise nearly 45,000 individuals.[3] Lantia Intelligence reports that the Sinaloa Cartel maintains operations in more than 100 municipalities nationwide, while the CJNG’s footprint extends to over 350 municipalities,[4] underscoring its broader territorial reach. States such as Baja California, Chihuahua, Guanajuato, Guerrero, the State of Mexico, Michoacán, and Morelos continue to exhibit particularly deep social and territorial entrenchment of organized criminal groups.[5]This concentration of criminal power limits the Sheinbaum administration’s policy options by reducing the effectiveness of fragmented enforcement and increasing the political risks of reform.

Map 1. Territorial Presence of Organized Criminal Groups (OCGs) Mexico 2024

Map prepared by Rajendra G. Kulkarni using QGIS 3.34 (https://www.qgis.org/). Sources: Lantia Intelligence and INEGI.

Beyond these dominant coalitions, Lantia Intelligence distinguishes between “mafias” and “bands.” Mafias are defined as regionally rooted organizations composed of armed groups that may function as contractors for major cartels or operate independently. The most prominent mafias include La Nueva Familia Michoacana, Unión Tepito, Los Zetas Vieja Escuela, Los Metros, and the Northeastern Cartel.[6] Bands, by contrast, are smaller armed groups or criminal cells. Some, such as Los Viagras, the Tepalcatepec Cartel, and the Guardia Michoacana, control significant territory, while others—such as the Nueva Plaza Cartel, Los Corazones, Los Páez, Mara Salvatrucha, the Tláhuac Cartel, and Los Rodolfos—are notable primarily for their membership size rather than territorial reach.[7]

Corruption remains a structural feature of Mexico’s criminal environment, shaping how threats are identified and significantly weakening the state’s capacity to respond to organized crime (local and transnational). Criminal investigations are often under-resourced and incomplete, coordination among security agencies remains uneven, and collusion between criminal organizations and public officials persists across multiple levels of government. These conditions translate into acute risks for local authorities operating in territories contested by criminal groups. The assassination of Carlos Manzo, a municipal leader targeted in a public setting, illustrates the continued vulnerability of local officials and the limited protective capacity of the state in areas where criminal power intersects with political authority.[8]

These dynamics are further compounded by deep and longstanding deficiencies within Mexico’s justice system, including weak prosecutorial capacity, low conviction rates, and limited accountability for crimes involving organized actors. Against this backdrop, the administration of President Claudia Sheinbaum has enacted a far-reaching judicial reform that introduces the popular election of judges, magistrates, and Supreme Court justices. While the reform is intended to enhance legitimacy and public accountability, it has also intensified concerns regarding judicial independence and exposure to political or criminal influence. Its effectiveness will ultimately depend on implementation—specifically, the presence of credible safeguards against capture, the integrity of judicial elections, and the ability of newly elected judicial actors to operate autonomously in high-risk environments marked by intimidation, political protection of crime, and violence.

Public discourse and media coverage of organized crime in Mexico continue to oversimplify violence by framing it as binary competition between rival “cartels” for drug routes or territorial control. This narrative is increasingly disconnected from current realities under the administration of Claudia Sheinbaum, where judicial restructuring, expanded security mandates, and evolving enforcement strategies have interacted with criminal adaptation. What are commonly described as cartels operate less as centralized hierarchies and more as transnational networks of semi-autonomous enterprises. These criminal corporations coexist with decentralized networks and franchise-like structures that adjust rapidly to policy change, enforcement pressure, market diversification, and shifting political conditions—producing more fragmented and persistent patterns of violence that are difficult to address through traditional, cartel-focused strategies.[9]

A network-based perspective is therefore essential for understanding organized crime in Mexico today. Contemporary criminal systems function as complex adaptive networks linking manufacturers, brokers, wholesalers, retailers, precursor suppliers, and a broad range of facilitators across borders—including actors based in the United States. These networks depend on corruption and collusion involving customs officials, law enforcement, political authorities, financial intermediaries, and armed enforcement cells. Under current conditions, governance choices in Mexico—including judicial reform and security centralization—interact with external pressures from the renewed Donald Trump agenda emphasizing border hardening and mass deportations, further reshaping criminal incentives and organizational forms. Viewed through this lens, organized crime in Mexico is not a static or monolithic threat but a fluid ecosystem shaped by policy decisions on both sides of the border, with direct implications for security outcomes and state capacity.[10]

Endnotes

[1] Source: National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI, for its acronym in Spanish): https://www.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/olap/proyectos/bd/continuas/mortalidad/defuncioneshom.asp?s=est.

[2] According to Lantia Intelligence, the Sinaloa Cartel is not limited to drug trafficking but is also involved in a range of other illicit activities, including extortion and money laundering. The consultancy reports that the CJNG exhibits a broader geographic footprint and operates across multiple illicit markets, including drug trafficking, extortion, arms trafficking, money laundering, fuel theft, contraband, human trafficking, and migrant smuggling. See Eduardo Guerrero Gutiérrez, “Con los cárteles, 44,800. ¿Son muchos o pocos?” El Financiero, 31 July 2023, https://www.elfinanciero.com.mx/opinion/eduardo-guerrero-gutierrez/2023/07/31/con-los-carteles-44800-son-muchos-o-pocos-1/.

[3] Ibid. Another study published in September 2023 in Science magazine calculates that all so-called Mexican cartels “collectively employ approximately 175,000 people,” making them the “fifth largest employer in the country.” See Sara Reardon, “Cutting cartel recruitment could be the only way to reduce Mexico’s violence.” Science, 21 September 2023, https://www.science.org/content/article/cutting-cartel-recruitment-could-be-only-way-reduce-mexico-s-violence.

[4] Eduardo Guerrero Gutiérrez, “Hasta 23,600 en el núcleo de ambos cárteles; y hasta 48,700 con grupos aliados.” El Financiero, 7 August 2023, https://www.elfinanciero.com.mx/opinion/eduardo-guerrero-gutierrez/2023/08/07/hasta-23600-en-el-nucleo-de-ambos-carteles-y-hasta-48700-con-grupos-aliados-22/.

[5] Lantia Intelligence, weekly briefing 129 (10–16 July 2023).

[6] Lantia Intelligence, weekly briefing 133 (7–13 August 2023).

[7] Lantia Intelligence, weekly briefing 134 (14–20 August 2023).

[8] Carlos Manzo Rodríguez, who served as the independent mayor (municipal president) of Uruapan, Michoacán, was killed during a public Day of the Dead celebration in November 2025. See Associated Press, staff (2025), “Organized crime believed involved in killing of popular Mexican mayor by teenage gunman.”Associated Press, November 6, https://apnews.com/article/mexico-michoacan-mayor-uruapan-sheinbaum-afd5d70c3d372e9ac90a924ac9672e72.

[9]These ideas are explained in my forthcoming book Cárteles Inc.– Una “Nueva Generación” (Siglo XXI Editores and PUEDJS-UNAM, 2026).

[10] Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera, “The Myth of the Mexican ‘Cartels.” Small Wars Journal, 17 April 2023, https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/perspective-myth-mexican-cartels.

The post Transnational Organized Crime in Mexico: Continuity, Change, and Uncertainty under the Sheinbaum Administration (Part I) appeared first on Small Wars Journal by Arizona State University.

Related Articles

Swizerland’s Loïc Meillard dominates alpine skiing at Milan–Cortina Games

Switzerland’s Loïc Meillard led a commanding display in men’s alpine skiing at...

US deploys 100 soldiers to Nigeria as attacks by armed groups surge

US soldiers will not have a combat role and are to operate...

In Hungary, Marco Rubio Stresses Trump’s Support for Viktor Orban

The U.S. secretary of state said in Budapest that the president was...

Macron visits India to deepen defence ties and AI cooperation

French President Emmanuel Macron arrives in India on Tuesday for a three-day...

Leave a comment