Beyond Swarming: Documenting Harassment, Assault, and ICAD by Chinese Maritime Militia

Abstract: This article documents the escalating use of the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM) by China to assert territorial claims in the South China Sea through “gray zone” tactics, recording 270 specific incidents of harassment and assault since 2012. By analyzing the militia’s strategic coordination with the Chinese Coast Guard and its impact on regional sovereignty, the research seeks to strip away the shroud of deniability and provide quantifiable evidence of state-backed maritime coercion.

Waving axes and boarding Filipino vessels, blue hulled fishing ships cutting dangerously close to coast guard ships, subsea cables getting cut to Taiwan, and sailors attacked in the night: we see these stories regularly in our news feeds and sound bites condemning them in defense podcasts. Videos of the destruction and chaos they sow serve as reminders of the ledge the United States (U.S.) is on in the South China Sea (SCS). The Chinese maritime militia (also known as the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia or PAFMM) are more than an internet video or news story. To thousands of Filipino, Vietnamese, Malaysian, Indonesian, and Bruneian fishermen, the Chinese maritime militia is a very real threat to their livelihood, property, and lives. They are an almost daily reminder of China’s growing presence in the region. While some stories might make it to the news, there has been no concerted effort to document open source reports of Chinese maritime militia violence against their neighbors in the South China Sea until 2025. Over the last thirteen years, there have been 270 documented maritime incidents of Chinese militia vessels harassing, assaulting, or using ICAD – illegal, coercive, aggressive, and deceptive behavior against states in the SCS. China and its Maritime Militia leverage uncertainty and gray zone aggression to assert themselves in the region, achieve their geopolitical aims of increased regional influence, and secure access to the vast economic and material wealth in the SCS. China accomplishes these objective by using both conventional and gray zone tactics to achieve strategic success while minimizing risk and maintaining deniability, all with little resistance. This article and other research seeks to address this lack of resistance by shedding light on militia activity, providing quantifiable evidence of aggression, and showing militia ties with the Chinese Coast Guard.

The South China Sea

At approximately 3.5 million square-kilometers, the South China Sea is rich in resources, containing 10% of the region’s aquatic food supply, 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, 17 billion barrels of proven and probable oil reserves, valuable minerals, and a critical trade route through which roughly 50% of global commerce passes. To China, the SCS is vital to its import-dependent economy, export-driven growth, and regional/global ambition of national rejuvenation. The contest for these resources and this region covers multiple aspects of national power: economic coercion, military operations, and international diplomacy at the United Nations.

Despite the value of the SCS, conflict is extremely risky. Full-scale war in the SCS would result in disrupted food supplies, economic downturn, and regional instability. These risks are not in the best interest of any state actor, but the potential gains certainly are. To access the mineral, energy, and substantial natural wealth while avoiding conflict, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has resorted to employing gray zone tactics through irregular forces and maritime militias. Gray zone operations exist in a “no-man’s-land between peace and war,” executed deliberately with specific goals in mind but “without the overt use of military force”. Gray zone methods allow the actor to maintain deniability and forces adversaries to confront difficult choices: how to respond, whether to shift force posture, and how to allocate scarce resources against irregular forces. The PRC uses gray zone tactics and irregular forces to achieve its political objectives in a way that avoids confrontation with the United States while still eroding its credibility. China uses “salami slicing” tactics to seize islands, atolls, reefs and attempts to unilaterally impose its nine-dash line across SCS in a “War without Gun Smoke”. For China, the best tool for providing coercive force below the threshold of war is their People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia.

The Maritime Militia

For war the militias prepare to conduct supporting tactical tasks to disrupt the tempo of operations, time tables or actions of adversaries, delay their arrival or even redirect targets to more disadvantageous sea space. In peace-time operations they are seen alongside fishery enforcement vessels and Chinese Coast Guard ships conducting territorial policing, surveillance, rescue, and sovereignty enforcement.

Officially labeled the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM) by the Congressional Research Service, this force constitutes an emerging threat to America, its allies and its interests in the region. For decades, Chinese militia in the SCS operate in plain sight alongside thousands of commercial fishing, exploration, and policing agencies. Evolving out of the collectivization of fishing communities under Mao Zedong and early coastal defense policy, the maritime militia plays a supporting role to China’s conventional forces. Like other state militias, they can operate both alongside state security and independent of direct state oversight. They are often seen operating on the peripheries of conventional units in preparation for war but also in support of peace. For war the militias prepare to conduct supporting tactical tasks to disrupt the tempo of operations, time tables or actions of adversaries, delay their arrival or even redirect targets to more disadvantageous sea space. In peace-time operations they are seen alongside fishery enforcement vessels and Chinese Coast Guard ships conducting territorial policing, surveillance, rescue, and sovereignty enforcement.

Officially labeled the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM) by the Congressional Research Service, this force constitutes an emerging threat to America, its allies and its interests in the region. For decades, Chinese militia in the SCS operate in plain sight alongside thousands of commercial fishing, exploration, and policing agencies. Evolving out of the collectivization of fishing communities under Mao Zedong and early coastal defense policy, the maritime militia plays a supporting role to China’s conventional forces. Like other state militias, they can operate both alongside state security and independent of direct state oversight. They are often seen operating on the peripheries of conventional units in preparation for war but also in support of peace. For war the militias prepare to conduct supporting tactical tasks to disrupt the tempo of operations, time tables or actions of adversaries, delay their arrival or even redirect targets to more disadvantageous sea space. In peace-time operations they are seen alongside fishery enforcement vessels and Chinese Coast Guard ships conducting territorial policing, surveillance, rescue, and sovereignty enforcement.

China defines the PAFMM as “an armed mass organization composed of civilians retaining their regular jobs,” therefore classified as both a component of China’s armed forces and an “auxiliary and reserve force” of the Peoples Liberation Army. These vessels operate under the direction of PRC civil and military leaders, not as lone actors. While ostensibly operating as fishing vessels, these units are recruited and equipped by provincial governments based on requirements provided by Provincial Military Districts and the policy of the Central Military Commission’s National Defense Mobilization Department. This resourcing and support creates a direct link between the maritime militias and the central government/military; all financing, manning, training, equipment, and missions are nested within the broader structure of the PLA. This allows the militia to augment the Chinese military by acting as a force multiplier, enabling the PLA to assert greater control over “maritime territory” while maintaining deniability and mitigating any negative ramifications. By leveraging gray zone warfare, the PRC can achieve its military aims of greater control and posture in the SCS, political aim of keeping competition below kinetic or conventional conflict, and economic aim of increasing access to the abundant natural resources.

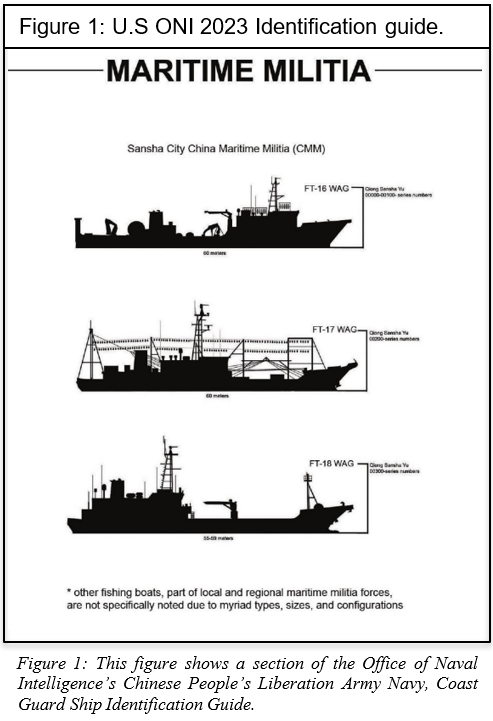

Individual PAFMM unit composition, proficiency, and characteristics are highly dependent on their provincial district and military district. Militias operating in the SCS are based primarily across ten ports in Guangdong and Hainan. Because of the differentiation in mission sets, resourcing, and training, the PAFMM fleet can be broken into two categories: normal fishing vessels with PLAN support, and purpose-built militia vessels. To further enhance their effectiveness, the PRC professionalizes these units by providing funds from national defense budgets for training and equipment. This military training increases effectiveness in sea-borne operations such as border patrol, surveillance and reconnaissance, maritime transportation, and search and rescue. PRC-provided equipment ranges from satellite communication terminals and shortwave radios to nonlethal weapons such as water cannons and modified ship hulls designed for ramming other vessels. With 304 confirmed vessels and potentially thousands more in support, the U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence updated its Identification Guide to include a variety of PAFMM vessels, highlighting the conventional importance of these militia vessels.

Once activated, these irregular forces fall under the authority of the local People’s Armed Forces Departments (PAFD), China Coast Guard (CCG), PLAN, or another maritime-related government entity. Activations occur in response to natural disasters, search and rescue, coastal patrolling, or defense of sovereign claims. The mobilized PAFMM becomes a force multiplier for the PRC and PLA in “military operations other than war (MOOTW)”, using “military-civil general-purpose equipment” to assist conventional forces. These MOOTW actions mirror gray zone operations. Examples of known and well-documented operations include the harassment of the USNS Impeccable, the standoff at Scarborough Shoals in 2012, and the swarming by 135 Chinese Maritime Militia (CMM) vessels of Julian Felipe Reef in 2023.

While there exists a broad array of well-researched and documented analysis of the PAFMM, no comprehensive recording of militia activity exists. The Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) provides incredible work documenting the presence of vessels, but not their specific activities. The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) captures Coast Guard activity, which sometimes includes militia vessels but has not focused effort on militia activities. This project captures instances of confrontation between suspected Chinese maritime militia vessels and other parties – defined as any actor not affiliated with the PRC – to fill this research gap. Confrontation is defined as any occurrence of the following: (1) harassment – stalking, conducting hazardous navigation operations, interception, blocking passage, loitering in passageways, short duration (less than 24 hours) swarming to deny legal operation, unlawful detention; (2) assault (simple or aggravated) – ramming, emplacement of obstacles with the intent to damage property, damage to property, use of nonlethal weapons (lasers, water cannons, acoustic weapons); (3) ICAD – rafting, military operations (reconnaissance, disruption, deception), or other CMM activities that fall below the threshold of harassment but within the context of gray zone operations. As part of a larger research project on PAFMM activity, the data below show the employment of web scraping technology and manual searches to collect and analyze incidents involving CMM from targeted websites, filtering results by specific keywords, geographic location, timeframe, and incident criteria to build a structured database. The results of this effort highlight the prolific use of the militia in China’s pursuit of national rejuvenation and greater regional power.

Militia Activity

This research shows that militias conduct swarming alongside kinetic and disruptive behavior, returning to the guise of innocent fishing vessels once they achieve their objectives.

To advance its political objectives in the South China Sea, the People’s Republic of China employs a broad, multi‑pronged strategy that leverages diplomatic pressure alongside paramilitary and military instruments of power. A central component of this approach over the past twelve years has been the Chinese maritime militia, which has played a important though largely hidden role in reinforcing Beijing’s sovereignty claims, projecting influence, and sustaining an almost continuous Chinese presence across this heavily contested region. Table 1 documents this activity, capturing 270 open‑source reports of harassment, assault, or interference with civilian access to disputed areas (ICAD) targeting Filipino and Vietnamese fisherfolk between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2025. On average, this equates to roughly a 5% likelihood of a militia‑related incident occurring on any given day over the last thirteen years. Figure 2 further illustrates the breadth of militia operations across the South China Sea, showing their extensive targeting patterns not only against Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam, Taiwan, and the Philippines but also against U.S. forces and key American allies, including Australia, India, and Japan.

Further analysis reveals that 48% of incidents occurred during joint militia and Chinese Coast Guard operations, indicating a high degree of coordination between these forces, strengthening the claims that the PAFMM serves as an extension of the PRC in the region. 34% percent of all recorded incidents took place between May and July, aligning with the PRC-imposed fishing ban in the SCS. This seasonal trend suggests that militia activity may strategically heightened during specific periods, potentially to enforce maritime claims under the guise of resource protection. These findings provide deeper insight into the structured and strategic nature of Chinese maritime militia operations, reinforcing the role of state-backed coercion in regional maritime disputes.

Table 1 and Figure 2 only represent cases of harassment, assault, ICAD and do not show swarming activity or the prolific use of militia. Given the gray zone context, this count is likely incomplete due to deception, underreporting, and the remote nature of many incidents. This research shows that militias conduct swarming alongside kinetic and disruptive behavior, returning to the guise of innocent fishing vessels once they achieve their objectives. The most telling example is at Second Thomas Shoal, where the infamous BRP Sierra Madre lies. Here, the tension between the Philippines and China is at its most severe. As shown in AMTI’s 2023 militia tracking, we see a continuous militia presence at Second Thomas Shoal with up to twenty-one vessels present at times. Coinciding with this activity, thirteen incidents of harassment and two incidents of assault occurred in 2023, one of which caused “bodily injury, [and] damaged Philippine vessels” according to the U.S. Ambassador. Over the entire period analyzed, Second Thomas Shoal accounted for 29 reported incidents. Although this appears substantial, it is comparatively lower than Scarborough Shoal (43 incidents), the Paracel Islands (33), and Vietnam’s Exclusive Economic Zone (32)

Table 1 and Figure 2 only represent cases of harassment, assault, ICAD and do not show swarming activity or the prolific use of militia. Given the gray zone context, this count is likely incomplete due to deception, underreporting, and the remote nature of many incidents. This research shows that militias conduct swarming alongside kinetic and disruptive behavior, returning to the guise of innocent fishing vessels once they achieve their objectives. The most telling example is at Second Thomas Shoal, where the infamous BRP Sierra Madre lies. Here, the tension between the Philippines and China is at its most severe. As shown in AMTI’s 2023 militia tracking, we see a continuous militia presence at Second Thomas Shoal with up to twenty-one vessels present at times. Coinciding with this activity, thirteen incidents of harassment and two incidents of assault occurred in 2023, one of which caused “bodily injury, [and] damaged Philippine vessels” according to the U.S. Ambassador. Over the entire period analyzed, Second Thomas Shoal accounted for 29 reported incidents. Although this appears substantial, it is comparatively lower than Scarborough Shoal (43 incidents), the Paracel Islands (33), and Vietnam’s Exclusive Economic Zone (32)

Taken together, these incidents illustrate the militia’s diverse and escalating tactics as well as the broader trends that influence militia use.

While collecting incidents of militia use, this project identified several trends affecting both the occurrence and reporting of these incidents. First, an analysis of the collected data reveals a correlation between incidents and key events in the region. A notable example is the 42 incidents recorded in 2014 that correspond to a confrontation between Vietnam and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) over oil rights and the operation of the Haiyang Shiyou 981 oil rig. During this nearly three-month confrontation (from May 2 to July 15, 2014), approximately 190 vessels from both China and Vietnam engaged in near daily reciprocal gray-zone actions until the Chinese vessels departed the area in mid-July. The next two key events concern political administration and contrasting incident reporting in Manila. Rodrigo Duterte, President of the Philippines (2012-2022) adopted a conciliatory approach toward China, while Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. (2022-Present) adopted an aggressive policy of transparency against the PRC and aligned with the United States. These contrasting policies explain the decrease in reporting during Duterte’s administration and the significant increase in transparency and reported incidents under Marcos.

Reported incidents range in their intensity and ramifications. Some eighty-one cases in our analysis involved some form of assault, such as a June 2019 incident where a Chinese vessel collided with and sunk a Vietnamese fishing boat leaving 22 sailors adrift at sea. This is an extreme case and most often assault results in lesser property damage, such as the case of Chinese militia vessels repeatedly ramming a Vietnamese fishing vessel in May 2013 or the sideswiping of a Filipino patrol boat in 2024. 106 incidents involved some form of harassment such as dangerous maneuvers or blocking access. On the lowest end of the gray zone spectrum are the 82 occurrences of ICAD, however these events are difficult to capture and it is often challenging to conceptualize their linkage to militia activity. However, the colocation of two militia vessels observing Balikatan 2024, or the surrounding of a Filipino vessel by CMM vessels during a resupply mission are two examples of suspicious and deceptive use of militia vessels. Taken together, these incidents illustrate the militia’s diverse and escalating tactics as well as the broader trends that influence militia use.

Conclusion

This research project sheds light on the complex dynamics of maritime militias in the South China Sea and how the People’s Republic of China uses them to expand its maritime claims, control territory, and ultimately increase its regional power. Left unchecked, irregular forces operating in the gray zone undermine global stability, regional economies, and can inadvertently escalate to war. Over the last thirteen years, 270 incidents of harassment, assault, and ICAD reveal a persistent pattern of coercive behavior and highlight the structured and strategic nature of militia operations. The PAFMM operates as an extension of state power, utilizing gray-zone tactics to advance territorial claims while maintaining deniability. It is essential to confront malign actors who employ gray zone tactics to reduce their effectiveness and expose their methods. By challenging these operations, we limit the ability of irregular forces to act in obscurity. The greatest strength of this project is raising awareness about the use of militias and encouraging regional actors to act. It serves as a call to confront these threats as they emerge, ensuring they cannot operate unchecked. Denial or misinformation does not degrade its value because its ultimate goal is awareness: taking maritime militias out of the shroud of gray zone operations and into public discourse.

The post Beyond Swarming: Documenting Harassment, Assault, and ICAD by Chinese Maritime Militia appeared first on Small Wars Journal by Arizona State University.

Related Articles

Indonesia’s Gaza gamble

Indonesia’s plan to send troops to Gaza could test its longstanding foreign...

2026 Olympics: France tie all-time medal record with 1 week left

France have earned their 15th medal at Milano Cortina, tying their all-time...

Cognitive Warfare Fails the Cognitive Test

This article is a re-publish of a critique of Frank Hoffman’s Assessing...

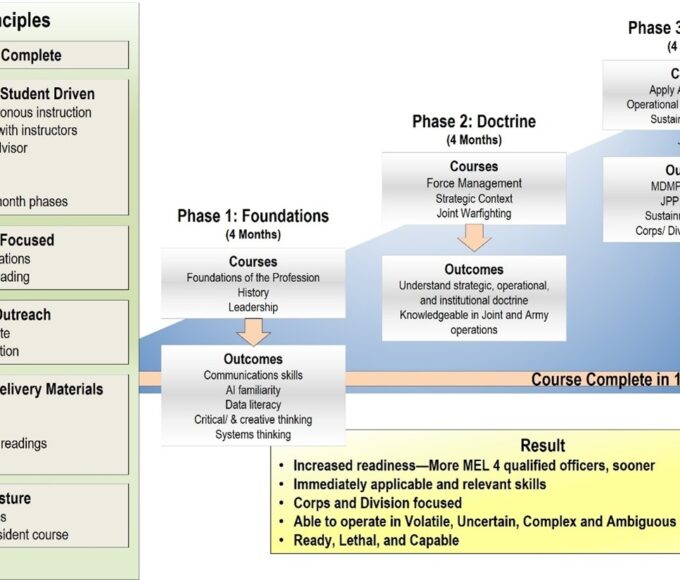

Driving PME Transformation for the Total Force: CGSS’s Modernization of the ADL Common Core

Abstract: The U.S. Army Command and General Staff College has comprehensively redesigned...

Leave a comment