- Home

- Advertise With us

- World News

- Tech

- Entertainment

- Travels & Tours

- Contact US

- About us

- Privacy Policy

Top Insights

Regular or Unleaded? Differentiating Irregular Warfare

Department of Defense Instruction 3000.07 defines Irregular Warfare with ambiguous criteria, including indirect approaches and asymmetric activities, which are also characteristic of conventional warfare. This lack of differentiating criteria complicates planning and approval processes. To provide a clearer distinction, this article proposes adding a complementary criterion, the level of state stewardship (state authority, entitlement, and responsibility), to differentiate state, or conventional, forces from irregular forces such as private militias, criminals, and disenfranchised groups. This model also proposes a model for visualizing and categorizing operations and activities within the spectrum of irregular and conventional warfare. Recognizing the presence of irregular forces in a contest will allow commanders to better apply the specific laws, authorities, and doctrines for supporting or targeting non-state forces.

In his work Cooperation in Change An Anthropological Approach to Community Development, Ward Goodenough explores the universal nature of cognitive structures, noting:

“Logic is in a formal sense a codification of the reasoning process, a set of rules of inference… In all societies, people not only reason, they judge one another’s reasoning as correct or incorrect. This means that in all societies there are generally accepted propositions about the manipulation of propositions. There is no society without a logic.”

Department of Defense Instruction 3000.07, Irregular Warfare (2025), provides commanders with definitions and policy guidance to conduct irregular warfare as a complement to other joint force activities, operations, and investments in competition and conflict. This instruction describes Irregular Warfare (IW) strategies and tactics as involving force or the threat of force for purposes other than physical domination over an adversary, and states, “IW is a form of warfare where states and non-state actors campaign to assure or coerce states or other groups through indirect, non-attributable, or asymmetric activities.” This imprecise definition may be perceived as allowing commanders considerable flexibility in categorizing operations as irregular warfare. However, it also introduces significant ambiguity into the mission-planning and approval process. Indirect, non-attributable, and asymmetric approaches were common in warfare long before strategists began debating whether warfare was irregular or hybrid. Because these characteristics are present in both regular and irregular warfare, they cannot be used to distinguish between the two. Commanders and planners may complement the DODI’s description of irregular warfare by including an additional characteristic in mission analysis: the participation of irregular forces in conflict or competition.

After catalytic converters became standard equipment in new cars in 1975, drivers of new vehicles could no longer use gasoline that contained lead without damaging their vehicle’s engines. The introduction of “unleaded” gasoline rendered “gasoline” a retronym. To differentiate fuel types, refiners and vendors added “Unleaded” alongside their newly relabeled “Regular” gasoline. The labels categorized the fuel and simplified fuel selection for drivers. Either the vehicle had a catalytic converter and required unleaded gasoline, or it did not have one and could burn regular gasoline. To use Aristotelian categorization, lead was either “Present-in” the fuel, or it was “Not Present-In” the fuel. Drivers could rapidly choose the appropriate fuel and return to the road.

Characteristics in Common

The criteria used to identify irregular warfare, as provided by DODI 3000.07, “through indirect, non-attributable, or asymmetric activities,” do not distinguish between types of warfare because these characteristics are present in both conventional and irregular warfare. Fabius Maximus employed an indirect strategy against Hannibal in 216 B.C., cutting supply lines and destroying foraging parties after the Roman defeat at Lake Trasimene to avoid direct conflict with Hannibal’s army. During the American Civil War, the Confederate Navy commissioned ships in Britain using false names, civilian crews, and shell companies, and attacked Union ships without attributing the action to the Confederacy. During the Battle of the Bulge in 1944, Germany’s 6th Panzer Army executed Operation Greif, sowing confusion behind Allied lines by altering rear-area road signs and spreading false orders. These efforts were considered warfare, neither conventional nor irregular.

People’s Liberation Army officers Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui describe “Unrestricted Warfare” as the use of armed and unarmed, military and civilian, and lethal and non-lethal means. Similarly, Lt. Col. Frank Hoffman, USMC Reserve (ret.) defines hybrid warfare as the simultaneous employment of conventional, irregular, and non-military tools to achieve strategic objectives, a world “in which machetes and Microsoft merge.” While both unrestricted and hybrid warfare are practical conceptual frameworks, neither is defined or even mentioned in the U.S. Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms (DoD Dictionary) or Joint Publication 3-0, Joint Campaigns and Operations. This article will therefore focus on differentiating conventional and irregular warfare.

To leverage the panoply of instructions, directives, doctrine, field manuals, techniques publications, and case studies available to guide mission planning and operational art in both conventional and irregular war, commanders must first identify differentiating criteria that distinguish types of warfare. As both ancient and modern warfare include indirect, non-attributable, and asymmetric activities, these criteria do not differentiate between them. Commanders require additional criteria to distinguish irregular warfare from conventional war to the standard necessary to apply operational law and policies.

Distinguishing Characteristics

Naval Postgraduate School guest lecturer Chief Warrant Officer “Duc” DuClos summarizes in Defining the Indefinable: A Critical Analysis of Current Irregular Warfare Doctrine” an assessment of irregular warfare doctrine and proposes an actor-based differentiation: are irregular forces a significant component in the conflict? To categorize the type of warfare in an operational area, commanders and staff may assess the environment to determine the extent to which irregular forces are, or could, influence the achievement of strategic objectives. Because the presence of irregular forces provides a present-in differentiation criterion, commanders may subcategorize specific operations and activities based on whether units will work through, with, or against irregular forces.

The differentiation between conventional and irregular warfare is not merely academic. State forces generally hold a force advantage against irregular forces, but also an information disadvantage. State officials are incentivized to leverage their relative advantages to overcome the insurgents’ information disadvantage. The opposite is true for irregular forces. As irregular forces cannot match the state’s overall force level, they must leverage their information advantage to achieve a strategic, temporary local force advantage, apply their limited force asymmetrically, and prevent coordinated state responses by avoiding attribution for activities harmful to the contested population. These characteristics are integral to irregular warfare, but not exclusive to it. “The first, the supreme, the most far-reaching act of judgement that the statesman and commander have to make is to establish by that test the kind of war on which they are embarking, neither mistaking it for, nor trying to turn it into, something that is alien to its nature.”

Systems theory (open or closed) approaches may further highlight the conceptual differences between irregular and regular or conventional warfare. Conventional warfare would most closely resemble a closed system, characterized by rigid hierarchical chains of command and low permeability to external system information beyond what is necessary for action. Behavior is internally determined by a closely followed doctrine; it is self-contained. Conversely, irregular warfare is an open system. For example, irregulars are part of the environment rather than an internal component of the conventional force. Open systems are characterized by complex self-organizing interactions. The historical examples above featured self-organizing agents pursuing sponsors’ objectives through adaptive behavior. The British goal of attacking American ships was achieved with self-organizing irregulars.

Modeling Conflict

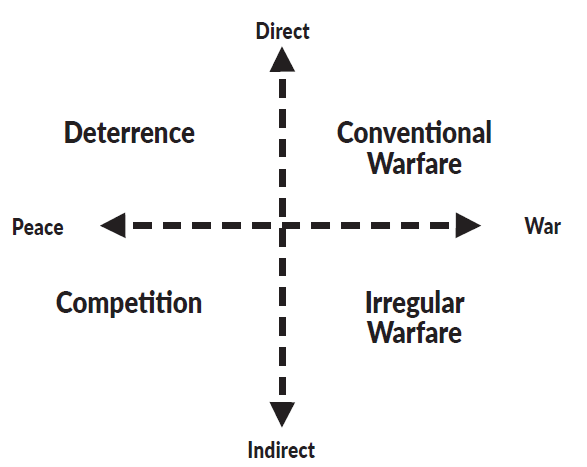

University of South Florida Senior Research Fellow Robert Burrell, in “Resilience and Resistance: Interdisciplinary Lessons in Competition, Deterrence, and Irregular Warfare,” proposed a Full Spectrum of Conflict Design Model to differentiate conventional and irregular warfare, as depicted in Figure 1. This model plots the extent to which operations and activities employ a direct or indirect approach on the Y-axis, and the degree of conflict, ranging from peace to war, on the X-axis. The intersection of these variables categorizes activities into quadrants: deterrence, conventional warfare, competition, and irregular warfare. This model categorizes irregular warfare as the intersection of indirect approaches and war.

Figure 1. Burrell’s Full Spectrum of Conflict Design Model

Because indirect approaches are not exclusive to irregular warfare, the model cannot, in practice, differentiate activities that correspond to doctrinal descriptions. In Figure 2, this model is used to categorize the construction of a school in a remote Afghan village in 2013 by U.S. Army Civil Affairs personnel. Because operators employed an indirect approach during wartime, their operations are plotted in the irregular warfare quadrant in contrast to the DoD Dictionary’s classification of these activities as civil-military operations. In Israel on the 7th of October, 2023, Hamas’s raids (operations “to temporarily seize an area to secure information, confuse an enemy, capture personnel or equipment or destroy a capability culminating with a planned withdrawal) upon Israeli security positions employed a direct approach in either peace or war depending on one’s assessment of the state of conflict between Israel and Hamas on the 6th of October. This would plot the attacks on this model in either the Conventional Warfare or Deterrence quadrants. Because the U.S. Department of State has designated Hamas as a terrorist organization, it defines these attacks as terrorism, not conventional warfare, despite Hamas’s employment of direct and asymmetrical approaches. The Military Information Support Task Force’s (MISTF) 2018 efforts in Afghanistan to influence public opinion in support of the elected government are modeled as Irregular Warfare, in contrast to the task force’s objectives.

Figure 2. Full Spectrum of Conflict Design Model in Application

To modify this model to differentiate regular from irregular warfare in a manner that plots activities in quadrants that match DoD Dictionary and doctrinal definitions, we can replace the direct/indirect approach of the Y-axis of the Full Spectrum of Conflict Design Model with the state’s level of authority, entitlement, responsibility, or state stewardship. Stewardship means the conduct, supervision, or management of something entrusted to one’s care. Stewardship denotes authority, responsibility, and the entitlement to perform duties commensurate with an office or position. Politicians assume authority upon taking office. A military officer has obligations under the oath sworn at commission and designated authority to execute their duties. Vested citizens have responsibilities associated with citizenship, such as paying taxes and responding to jury summons. Generally, as actors are granted more authority, more responsibility (and the public’s expectation of performance) follows. The level to which an individual is empowered or entitled by the state may be presented on a scale. Figure 3 illustrates a vertical scale of state stewardship, with state officials and officers at the top and reserve forces, city officials, and state employees in the upper middle. In the center are vested citizens and visa holders, often considered the “center of gravity” in irregular warfare. In the lower middle of the scale are undocumented immigrants and disenfranchised groups. At the bottom of the scale are criminals, insurgents, and foreign fighters, whose motives and actions may be counter to those of the state. Actors lower on the scale are granted fewer authorities and entitlements than those higher on the scale and are often less invested in and beholden to the state. They receive fewer of society’s benefits and therefore risk less when acting outside the community’s norms. In conflicts, combatants at the top of the scale are generally state-sponsored or “conventional” forces. Insurgents and resistance fighters from the bottom of the scale lack state sponsorship (or at least sponsorship from the nominally sovereign state) and are thus “irregular.”

Figure 3. Combatant State Stewardship

Figure 4 depicts this updated model again, using Civil Affairs, Hamas, and the MISTF in Afghanistan. When special operations Civil Affairs work with Afghan citizens to improve local infrastructure during war, these activities are conducted by state-sponsored combatants assisting vested citizens. They are, therefore, conventional civil-military operations despite the use of an indirect approach during active conflict. The MISTF’s attempts to sway the Afghan population to counter propaganda and support the Afghan government are also a form of conventional warfare, even when employing an indirect approach, non-attributable elements, and exploiting asymmetry between forces. Hamas’s attacks upon Israeli security outposts are not conventional warfare, despite their direct approach applied to a state-sponsored force, because Hamas is recognized as a terrorist organization by the U.S. Department of State and lacks recognized state sponsorship. These attacks are therefore irregular warfare, competition, or terrorism, not conventional warfare or deterrence.

Figure 4. The Spectrum of Conflict Model, with Combatant State Stewardship as the Y-Axis

The elements that characterize a raid (i.e., temporarily seizing an area with a planned withdrawal) remain unchanged across different categories of forces. A guerrilla force raid on a government outpost constitutes irregular warfare, even when the raid employs direct methods, because irregular forces conduct the raid. A raid by state forces upon an insurgent command nexus is irregular warfare because the targets are irregular forces. The presence of irregular forces provides a present-in differentiation criterion for subcategorizing conflicts as conventional or irregular, complementing the use of indirect approaches, asymmetric techniques, and the avoidance of attribution.

A given operational area may feature more than one type of warfare simultaneously. Just as a task force may clear insurgents in one district, hold in another, and build governance structures in a third while supporting counterinsurgency, a task force commander may order one unit to pursue conventional lines of operation against an adversary’s state forces and a second unit to lead irregular forces in supporting attacks. Both units may execute both direct and indirect operations against the enemy. The presence of irregular forces in the second unit’s operations renders its warfare irregular.

Conclusion

“Our language provides us with a set of percepts that serves as a code for other percepts.” Words, whether written or spoken, are icons or signs that represent ideas or concepts. Our ability to collaborate and coordinate our activities depends on our shared understanding of words. In any activity, from refueling a vehicle to sports, business, and warfare, the words we use help identify actions appropriate to the conditions and to apply the rules of the environment to achieve objectives. Labels like “Unleaded” helped drivers select fuel for their vehicles compatible with the vehicle’s equipment. Assessing the extent of state stewardship, recognition, and entitlement granted to combatants can help commanders identify the presence of irregulars and appropriately categorize their operations and activities. Recognizing the presence of irregular forces in a contest may allow commanders and staff to leverage the distinct laws, authorities, and procedures required to support or target non-state forces.

The post Regular or Unleaded? Differentiating Irregular Warfare appeared first on Small Wars Journal by Arizona State University.

Related Articles

A Worrying Military Build-up in the Western Balkans?

Europe’s most fragile region is not sleepwalking toward war, but it is...

Alysa Liu Is Skating Again, Her Way This Time

At 16, out of love with the sport, Liu stepped away. Controlling...

Former South Korean President Yoon gets life sentence for imposing martial law

Former President Yoon Suk Yeol was sentenced to life in prison for...

Today in Spain: A roundup of the latest news on Thursday

Spain extends residency rights for Ukrainian refugees, Barcelona to give over-55s €400...

Leave a comment