- Home

- Advertise With us

- World News

- Tech

- Entertainment

- Travels & Tours

- Contact US

- About us

- Privacy Policy

Top Insights

Confidence, Interoperability, and the Limits of U.S. Decision Systems

OPINION — In recent months, U.S. policy debates have increasingly acknowledged that the decisive contests of the 21st century will not be fought primarily on conventional battlefields. They will be fought in the cognitive domain, through influence, perception, legitimacy, and decision velocity. This recognition is important and depends on an adequate technical and institutional layer to deliver durable strategic advantage. Cognitive advantage cannot be declared. It must be engineered.

Today, the United States does not lack data, expertise, or analytic talent. What it lacks is decision-shaping architecture capable of producing consistently high-confidence strategic judgment in complex, adaptive environments. The result is a persistent gap between how confident U.S. decisions appear and how reliable they are – especially in Gray Zone conflicts where informal networks, narrative control, and societal resilience determine outcomes long before failure becomes visible. Afghanistan was not an anomaly. Nor will it be the last warning.

The Confidence Illusion

In U.S. national security discourse, the phrase “high confidence” carries enormous weight. It signals authority, rigor, and analytical closure. Yet extensive research into expert judgment, including studies of national-security professionals themselves, shows that confidence is routinely mis-calibrated in complex political environments.

Judgments expressed with 80–90 percent confidence often prove correct closer to 50–70 percent of the time in complex, real-world strategic settings. This is not a marginal error. It is a structural one.

The problem is not individual analysts. It is how institutions aggregate information, frame uncertainty, and present judgment to decision-makers. While pockets of analytic under confidence have existed historically, recent large-scale evidence shows overconfidence is now the dominant institutional risk at the decision level.

Recent U.S. experience from Iraq to Afghanistan suggests that institutional confidence is often declared without calibration, while systems lack mechanisms to enforce learning when that confidence proves misplaced. In kinetic conflicts, this gap can be masked by overwhelming force. In Gray Zone contests, it is fatal.

Afghanistan: Studied Failure Without Learning

Few conflicts in modern U.S. history have been studied as extensively as Afghanistan. Over two decades, the U.S. government produced hundreds of strategies, assessments, revisions, and after-action reviews. After the collapse of 2021, that effort intensified: inspector general reports, departmental after-action reviews, congressional investigations, and now a congressionally mandated Afghanistan War Commission.

The volume of analysis is not the problem. The problem is that these efforts never coalesced into a unified learning system. Across reports, the same lessons recur misjudged political legitimacy, overestimated partner capacity, underestimated informal power networks, ignored warning indicators, and persistent optimism unsupported by ground truth. Yet there is no evidence of a shared architecture that connected these findings across agencies, tracked which assumptions repeatedly failed, or recalibrated confidence over time.

Lessons were documented, not operationalized. Knowledge was archived, not integrated. Each new plan began largely anew, informed by memory and narrative rather than by a living system of institutional learning. When failure came, it appeared suddenly. In reality, it had been structurally prepared for years.

The Cipher Brief brings expert-level context to national and global security stories. It’s never been more important to understand what’s happening in the world. Upgrade your access to exclusive content by becoming a subscriber.

Reports Are Not Learning Systems

This distinction matters because the U.S. response to failure is often to commission better reports. More detailed. More comprehensive. More authoritative. But reports – even excellent ones – do not learn. Learning systems require interoperability: shared data models, common assumptions, feedback loops, and mechanisms that measure accuracy over time. They require the ability to test judgments against outcomes, update beliefs, and carry lessons forward into new contexts. Absent this architecture, reports function as historical records rather than decision engines. They improve documentation, not confidence. This is why the United States can spend decades studying Afghanistan and still enter new Gray Zone engagements without demonstrably higher confidence than before.

Asking the Wrong Questions

The confidence problem is compounded by a deeper analytic flaw: U.S. systems are often designed to answer the wrong questions. Many contemporary analytic and AI-enabled tools optimize for what is verifiable, auditable, or easily measured. In the information domain, they ask whether content is authentic or false. In compliance and due diligence, they ask whether an individual or entity appears in a registry or sanctions database. In governance reform, they ask whether a program is efficient or wasteful. These questions are not irrelevant, but they are rarely decisive.

Gray Zone conflicts hinge on different variables: who influences whom, through which networks, toward what behavioral effect. They hinge on informal authority, narrative resonance, social trust, and the ability of adversaries to adapt faster than bureaucratic learning cycles.

A video can be authentic and still strategically effective as disinformation. An individual can be absent from any database and still shape ideology, mobilization, or legitimacy within a community. A system can appear efficient while quietly eroding the functions that sustain resilience. When analytic systems are designed around shallow questions, they create an illusion of understanding precisely where understanding matters most.

DOGE and the Domestic Mirror

This failure pattern is not confined to foreign policy. Recent government efficiency initiatives-often grouped under the banner of “Department of Government Efficiency” or DOGE – style reforms – illustrate the same analytic tendency in domestic governance. These efforts framed government primarily as a cost and efficiency problem. Success was measured in budget reductions, headcount cuts, and streamlined processes.

What they largely did not assess were system functions, hidden dependencies, mission-critical resilience, or second-order effects. Independent reviews later showed that efficiency gains often disrupted oversight and weakened essential capabilities – not because reform was misguided, but because the wrong questions were prioritized. DOGE did not fail for lack of data or ambition. It failed because it optimized what was measurable while missing what was decisive. The parallel to national security strategy is direct.

Why Gray Zone Conflicts Punish Miscalibration

Gray Zone conflicts are unforgiving environments for miscalibrated confidence. They unfold slowly, adaptively, and below the threshold of overt war. By the time failure becomes visible, the decisive contests – over legitimacy, elite alignment, and narrative control – have already been lost.

Adversaries in these environments do not seek decisive battles. They seek to exploit institutional blind spots, fragmented learning, and overconfident decision cycles. They build networks that persist through shocks, cultivate influence that survives regime change, and weaponize uncertainty itself. When U.S. decision systems cannot reliably distinguish between what is known, what is assumed, and what is merely believed, they cede cognitive advantage by default.

What “90 Percent Confidence” Actually Means

This critique is often misunderstood as a call for predictive omniscience. It is not. According to existing standards, No system can achieve near-perfect confidence in open-ended geopolitical outcomes. But research from forecasting science, high-reliability organizations, and complex systems analysis shows that high confidence is achievable for bounded questions – if systems are designed correctly.

Narrowly scoped judgments, explicit assumptions, calibrated forecasting, continuous feedback, and accountability for accuracy can push reliability toward 90 percent in defined decision contexts. This is not theoretical. It has been demonstrated repeatedly in domains that take learning seriously. What the U.S. lacks is not the science or the technology. It is the architecture.

Cognitive Advantage Requires Cognitive Infrastructure

The central lesson of Afghanistan, Gray Zone conflict, and even domestic governance reform is the same: data abundance without learning architecture produces confidence illusions, not advantage.

Cognitive advantage is not about thinking harder or collecting more information. It is about building systems that can integrate knowledge, test assumptions, recalibrate confidence, and adapt before failure becomes visible.

Until U.S. decision-shaping systems are redesigned around these principles, the United States will continue to repeat familiar patterns – confident, well-intentioned, and structurally unprepared for the conflicts that matter most.

The warning is clear. The opportunity remains with Yaqin.

The Cipher Brief is committed to publishing a range of perspectives on national security issues submitted by deeply experienced national security professionals.

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspective and analysis in The Cipher Brief because national security is everyone’s business.

Related Articles

Trump’s ‘Board of Peace’ Said to Raise Billions in First Pledges for Gaza

The United Arab Emirates and the United States have each committed more...

DOJ Press Conference on Charges Announced against Chinese Nationals Involved in Sham Marriages

This press conference surveys charges against 11 individuals involved in a marriage...

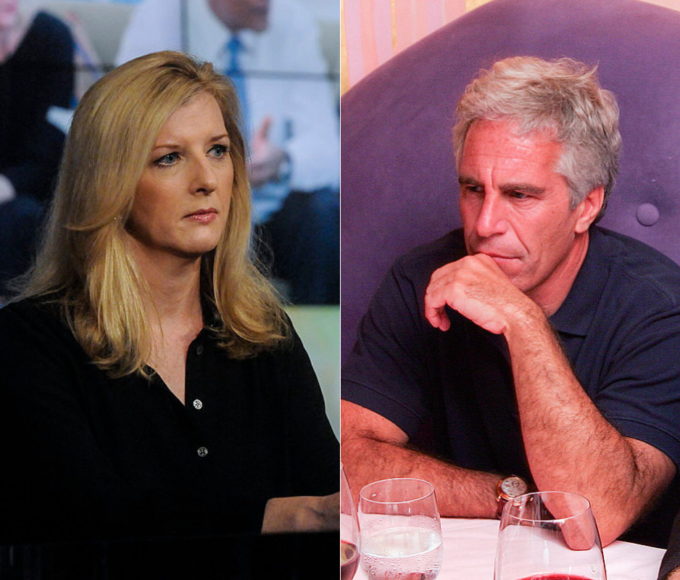

Epstein files fallout: People who’ve resigned or been fired after DOJ release

Kathy Ruemmler from Goldman Sachs is one of the latest to leave...

The Mutually Beneficial Ties Between Jeffrey Epstein and Thorbjorn Jagland

Thorbjorn Jagland, a former prime minister of Norway who led the Nobel...

Leave a comment