- Home

- Advertise With us

- World News

- Tech

- Entertainment

- Travels & Tours

- Contact US

- About us

- Privacy Policy

Top Insights

A La Carte Feminism: The Limits of NATO’s WPS Commitments in a Time of Crisis

As NATO marked its 75th anniversary and the 25th anniversary of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325, the Alliance’s renewed focus on the Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) agenda presents both symbolic commitment and practical challenges. This article evaluates NATO’s 2024 WPS policy in the context of its four strategic objectives—gender-responsive leadership and accountability, participation, prevention, and protection—highlighting persistent implementation gaps across member states. Drawing on national action plans, gender equality indices, and internal diversity reporting, the analysis identifies inconsistencies in policy execution, data transparency, and institutional accountability.

Introduction

NATO celebrated its 75th anniversary during the NATO Summit July 2024 in Washington, D.C., highlighting the Alliance’s implementation of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325, Women, Peace, and Security (WPS). October 2025 will mark 25 years since UNSCR 1325’s adoption.

NATO adopted its first WPS policy in 2007, action plan in 2021, incorporated WPS into its Strategic Concept, and its latest policy in July 2024. NATO focuses on four WPS strategic objectives: gender responsive leadership and accountability, participation, prevention, and protection.

However, gaps remain where progress and accountability are needed to achieve these goals. This analysis will compare objectives in relation to NATO member rankings on gender equality and WPS indices, the existence of members’ WPS national action plans (NAPs) and the transparency and progress of NATO’s Diversity and Inclusion Reports, identifying areas of improvement. Additionally, it will also review public criticisms of NATO’s limited engagement on WPS in Ukraine, Sweden’s shift from a feminist foreign policy, LGBTQ+ security challenges, and the rise of anti-gender movements in Europe, which the new policy must address.

NATO’s WPS Strategic Objectives

NATO’s 2024 WPS policy links its 2022 strategic concept goals and aims to integrate WPS across its three core tasks: deterrence and defense, crisis prevention and management, and cooperative security. The policy emphasizes gender mainstreaming, which NATO defines as “a strategy for making the concerns and experiences of both women and men an integral dimension of the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of policies, programs and military operations.” A summary follows NATO’s four WPS objectives and the challenges in their implementation:

Gender Responsive Leadership and Accountability: NATO’s first WPS objective seeks to ensure gender-responsive leadership by strengthening gender expertise, promoting gender equality and holding leaders accountable for WPS agenda implementation. While NATO has introduced policies, NAPs, training requirements and gender advisors, data collection remains opaque and there is limited evidence of security benefits. This will not change the “male- dominated security sphere” with needed “deep-rooted and radical integration. Requiring training on gender will promote greater understanding of why WPS is important beyond operational effectiveness and address broader equality concerns. NATO should mandate training on WPS for partners to encourage the recognition of gender rights as human rights.

Leaders need to recognize that being gender responsive is not just about women. Morrison (2023) wrote that NATO’s revised Bi-Strategic Command Directive 40-001 (2017) included men and boys in gender discussions to reduce resistance to gender mainstreaming at the operational and tactical levels.

Women In International Security (WIIS) and other practitioners stated the need for more male policymakers’ engagement in gender-responsive leadership and accountability and to challenge “men to engage with women and treat women as rights holders rather than as passive recipients.

Leaders need to recognize that being gender responsive is not just about women.

Participation: NATO aims for gender parity in its workforce, especially in leadership and decision-making roles, but none of its member states have achieved parity in parliamentary representation. A 2023 article on NATO’s future points out that while the percentage of women in member forces doubled from 5.9% in 2001 to 12% in 2019, parity remains elusive. NATO’s WPS integration is predicated on gender becoming a key part of leadership approaches and the goals to diversify that leadership must have accountability.

NATO aims for gender parity in its workforce, especially in leadership and decision-making roles, but none of its member states have achieved parity in parliamentary representation.

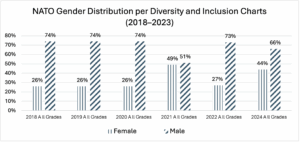

According to the 2023 Georgetown Institute of Women Peace and Security’s index, Iceland leads with 47.6% representation, while Hungary trails with 13.1%. Despite an increase in women within NATO and senior leadership roles, gender parity is only reached at the lower grades. The 2018-2022 Annual Diversity and Inclusion Reports (now the 2024 Diversity Balanced Scorecard) from NATO indicate inconsistent data collection, hindering tracking progress over time. (See NATO Country Findings table for additional analyses).

Women in International Studies (WIIS) held a sideline event during the July 2024 NATO summit, highlighting women’s leadership in the Alliance and the need to create more defense leadership roles for women and incorporate diverse voices in strategic decisions.

Prevention: This objective seeks to prevent and counter threats that disproportionately affect women and girls and promote their participation in crisis prevention and management. NATO’s performance in Afghanistan had difficulties with this objective as women were excluded from peace negotiations. Henderson (2023) noted NATO focused on increasing women in the military rather than their participation in peace negotiations.

In 2023, women made up just 16% of negotiators, declining for two consecutive years. NATO does not currently provide any gender disaggregated data on participants for peace processes or political talks. NATO’s commitment to “strengthen efforts to integrate gender perspectives into all aspects of its work” would be well demonstrated if data were provided on how women participate in the prevention of crises and crises management.

The PeaceRep PA-X Peace Agreement Database reports that in 2022, only 6 of 18 peace agreements (33%) referenced women or gender, and only one was signed by a representative of a women’s group. Researchers argue that this falls short of “UNSCR 1325’s ambition to adopt a gender perspective when negotiating and implementing peace agreements. The focus on training and capacity-building may have overlooked the need to address entrenched norms that view conflict as “exclusively the business of men,”

Protection: On June 19, 2024, the NATO International Military Staff Office of the Gender Advisor hosted a session on conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV). The discussion emphasized the importance of combatting CRSV with localized control of the process and highlighted NATO’s role in protecting men and boys from CRSV, noting those policies need strengthening (See GenderHub project on Men, Peace and Security). The May 2024 NATO Parliamentary Assembly recognized that NATO needs to strengthen relations with the Global South to check Russian and Chinese influence and reduce “sexual violence in conflict”.

NATO’s 2024 WPS policy sees CRSV as a deliberate tactic of war and that it is “committed to ensure effective prevention and response to CRSV in all NATO missions, operations and activities”. It pledges to protect women and girls from GBV and has expanded this to address technology-facilitated GBV, or TFGBV. (See details in the New Themes section). However, this protection is not explicitly extended to the LGBTQ community, although NATO has implemented internal programs in this regard. (See LGBTQ+ Policies).

NATO Allies often lack support services for conflict-related sexual, gender-based violence (CR-SGBV) and domestic violence.

While NATO has shown advances in the protection objective, Clarkson, McAnally and McInnis revealed that NATO Allies often lack support services for conflict-related sexual, gender-based violence (CR-SGBV) and domestic violence. They suggest that NATO should have learned CR-SGBV lessons from Afghanistan, the Balkans and Iraq. The U.N. Special Rapporteur 2024 report on violence against women and girls and Afghanistan’s human rights echoed these concerns: “The situation of Afghan women and girls is becoming increasingly alarming, with impunity creating risks that the international community has not yet fully grasped”.

Highlighted Themes in NATO’s 2024 Policy

Two key concerns were highlighted at the NATO anniversary event: climate change and TFGBV.

The 2024 NATO WPS Policy identifies climate change as a “defining challenge of our time,” noting it will affect genders differently and therefore women are needed to help find solutions to climate change-related security challenges. Research from the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace, and Security (GIWPS) underscores the nexus of climate, conflict, and gender, declaring that climate change destabilizes political systems and aggravates underlying political, social and economic conditions, which potentially provoke increased or renewed conflict. However, missing from the participation strategic objective is the promotion of women’s leadership in climate-related conflict mitigation and prevention.

[M]issing from the participation strategic objective is the promotion of women’s leadership in climate-related conflict mitigation and prevention.

The second theme referenced at the anniversary event was digital and emerging technologies. While these technologies can support gender equality, they propagate biases and violence, particularly TFGBV. NATO recognizes that women and girls are disproportionately targeted by GBV, CRSV, human trafficking, and now TFGBV. Men and boys can also be victims of these types of violence and should be included in any WPS agendas on this issue.

In 2024, a GIWPS Policy Brief stated that 85% of women globally experience or witness online violence, with 20% of victims reporting that it led to offline violence. TFGBV disrupts WPS objectives and international peace and security by excluding women from positions of power through harassment, exacerbating existing GBV threats (e.g., CSRV is filmed for propaganda and blackmail), facilitates new types of violence (e.g., AI generation of sexually explicit deepfakes), and fuels radicalization and violent extremism used by far-right groups to recruit young men violence.

LGBTQ+ is a target for mis/disinformation and violence. A 2023 report from Strategic Communications Task Forces and Information Analysis, looked at how foreign actors, such as the KillNet Russian hacker group, target LGBTQ+ individuals, including releasing the identities of NATO-affiliated people registered on a gay dating site.

To effectively address TFGBV, NATO needs to include LGBTIQ+ considerations and not just binary gender in its analysis. GIWPS recommends NATO include a gender lens in digital transformation, address how technology exacerbates CRSV, online misogyny and radicalization, and research on TFGBV in conflict contexts.

NATO Gender Findings and Diversity Reports

NATO’s 2024 WPS policy places primary responsibility for the WPS agenda on member nations through their NAPs, security and defense strategies, and “commitments to broader international frameworks.” It stresses the importance of coherence between national and global efforts.

The Peacewomen.org. and Oursecurefuture.org NAP databases track WPS implementation across NATO member states. Additionally, the 2023 European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) Gender Equality Index and the GIWPS Index provide insights into NATO members’ gender rankings. (See chart). These databases serve as valuable tools for change, helping identify areas where NATO can push for stronger WPS commitments. WIIS research in 2024 adds support for this type of guidance, “We know that countries that mention the defense department…generally score higher on implementation.”

All NATO members except Türkiye and Hungary have NAPs. However, 14 out of 32, or 44%, have NAPs that are expired or outdated. NATO could leverage its influence to encourage members to update or create new NAPs, ensuring a commitment to WPS both internally and externally. In the EIGE index, all European NATO countries scored above 50%, with 30% in the top quarter (noting EIGE only collects data on European countries). GIWPS’s rankings, which cover all NATO countries, show an average score of 85%, with 90% in the top quarter of 177 nations. Türkiye ranks lowest among NATO members (99/177), scoring 66.5%, followed by Greece at 51/177 and 76.6%.

However, NATO’s own gender data reporting has been inconsistent. (See chart for side-by-side comparison.) The 2021 report removed “U grade” appointments but reintroduced them in 2022, reducing female representation to 26%. Starting in 2020, the report removed the breakdown by percentage of women overall and female senior leaders in 11 categories and added one category of “other,” which is not defined, making year on year comparisons nearly impossible.

To maintain accountability and transparency, NATO must improve the consistency of its gender data.

The NATO 2024 scorecard shows comparisons between 2021 and 2023, skipping the 2022 data, and uses categories for subunits that were not listed in previous reports. It excluded several grades and presented data only on international staff, showing 44% female representation. This contrasts sharply with the 27% reported in 2022, suggesting the figures may not reflect the entire NATO organization. To maintain accountability and transparency, NATO must improve the consistency of its gender data. Accurate, year-over-year data is crucial if NATO aims to lead by example in promoting full, equal, and meaningful participation of women in peace and security.

European Challenges for NATO WPS

Civil Society

NATO’s initial engagement with WPS in 2007 lacked consultation with civil society, but this changed in 2014 with the creation of the WPS Civil Society Advisory Panel (CSAP). Despite this, many within civil society organizations remain wary of engaging with NATO because of its military nature. A 2023 article revealed concerns from participants in CSAP about the lack of transparency and meaningful dialogue, lack of racial and inadequate funding. Additionally, some worry NATO may use women’s rights groups as intelligence tools.

Absence of WPS in Ukraine Response

NATO’s lack of a gender-focused response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine highlights challenges with WPS implementation. The 2024 NATO policy on WPS states that the “use of CRSV as a deliberate tactic of war is an acute threat in all conflicts”. The policy highlights how Russia used CRSV, unlawful killings and torture on Ukrainians, particularly on women and girls.

An analysis by Wright in 2022 noted that NATO did not express gender’s importance in its response, drawing attention to the “disjuncture between the rhetoric and reality of NATO’s commitment to the WPS agenda.” O’Sullivan, and Krulišová argued in 2023 that the international community, neglected to use WPS approaches to aid Ukraine. They claim the war places the WPS focus on external insecurity, and the silence is apparent evidence that the agenda is not suitable for full-scale war. “This failure to apply WPS when urgently needed relates to the deeper challenges surrounding the global WPS policy and practices,”. Despite supporting Ukraine’s WPS policy since 2014, NATO’s limited inclusion of WPS in its Ukraine response undermines its commitment to the agenda.

Sweden’s Abandonment of Feminist Foreign Policy

Sweden supported NATO in its WPS agenda, bringing the first gender advisor to the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe, and evaluating NATO’s 2012 WPS implementation in operations. In 2014, Sweden became the first country to adopt a feminist foreign policy (FFP). However, Sweden abandoned FFP in 2022 amid its bid for NATO membership following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This silence on FPP came before the October 2022 election of the new conservative government, which officially abandoned FPP and saw NATO membership as incompatible with the policy, even though NATO promoted WPS in its 2022 strategic concept.

Wright and Rosamund,(2024) attribute Sweden’s gendered silence partly to Türkiye and Hungary blocking Sweden’s membership forcing Sweden to sacrifice ideals to appeal to their “gendered nationalism.”

LGBTQ+ Policies

NATO has made internal progress supporting LGBTQ+ rights through initiatives such as Elevate Diversity, Proud@NATO and NATO’s diversity and inclusion program. NATO Secretary-General Stoltenberg publicly supportedLGBTQ+ rights: “LGBTQ+ people deserve respect & dignity, and I am proud to call myself your ally.” However, Hurley noted such statements describe identity rather than concrete action.

Despite policy advancements, NATO still adheres to a gender binary, as noted in a 2024 article by Security and Defence Quarterly. The researchers stated that despite having policies and practices promoting a diverse and inclusive workforce, the equal opportunity and diversity policy remains unenforced. Additionally, Botha revealed in 2021 that WPS does not adequately address LGBTQ+ vulnerabilities, especially in conflict zones where LGBTQ+ people face heightened violence and discrimination. LGBTQ+ identity has become part of what Hurley, defines as “value centered,” claims by states and alliances for foreign and security policy justification. Hurley’s article notes that LGBTIQ+ rights define states, international institutions, and their leaders as well as their relationships, “whether this be as ‘progressive allies’ in the case of NATO or as a defender of Mother Russia’s ‘traditional values’ against the ‘immorality’ of a corrupt West.”

Examining NATO Alliance member policies on LGBTIQ+ with such tools as the Global Acceptance Indexcould be the start of finding a baseline of where members are in terms of human rights and incorporating LGBTIQ+ into the WPS agenda. This would allow the issue to gain needed traction and support.

Gender Policy Backlash

NATO’s WPS agenda faces resistance from a growing “anti-genderism” movement that opposes gender equality and mainstreaming, particularly in countries such as France, Hungary, and Poland. This transnational movement has actors mobilizing people against women’s rights, reproductive services, marriage equality, sex education, gender studies, and gender mainstreaming, which are related to the WPS agenda and objectives.

The Global Action for Trans Equality organization notes that anti-gender movements aim to restrict human rights across multiple domains, from legal gender recognition to healthcare access. Walton, has reported on the movement, noting findings from the 2020 U.N. Human Rights report that cited conservative groups forming a “national and transnational alliance with shared strategies and objectives” to show that the concept of gender is dangerous, as it changes the ways societies are structured. This movement is found in many countries within NATO and poses a threat to the integration of gender equality.

A 2020 Foreign Policy Analysis article identifies a trend referred to as “remasculinization” in international politics, where male leaders and anti-gender political groups oppose gender equality and mainstreaming at the national level. Kotliuk (2023) argued the Soviet Union’s fall created a “remasculinization” gap that Putin was able to fill this gap with his hypermasculinity.

Gottzén and Berggren (2023) found young men in many Western states increasingly oppose women’s rights and gender equality, feeling marginalized and turning to misogynistic and far-right ideologies that will “remasculinize” them. The authors say this process is not just individual but societal, as masculinity is viewed as threatened by “non-whites, feminists, sexual minorities, and others, and therefore believes it needs to be reclaimed.” These global trends have disturbing implications for the WPS agenda and NATO’s WPS objectives. Structured discussion and policies to address anti-gender and remasculinization within NATO’s framework are needed, with a self-critical internal look on how its own structures and processes may be supporting or ignoring such movements.

Summary

NATO’s 2024 WPS Policy reaffirms the allies’ commitment to advancing the global WPS agenda, as outlined in UNSCR 1325 and subsequent resolutions. While NATO has made noteworthy progress, this advancement is grounded in policies but lacking in implementation and documentation. In 2023, Simone Benson, a researcher at the Centre for International and Defence Policy, emphasized that NATO’s success depends on the full integration and transparency of its WPS commitments. However, some Alliance members and partners selectively engage with the WPS agenda, a practice termed “a la carte WPS” by the Gender Hub.

NATO needs to hold all its members and partners accountable to the four WPS strategic objectives. Transparent data collection and consistent reporting by members and partners is essential for assessment. Additionally, European WPS challenges must be addressed in future discussions with concrete plans for mitigation. At NATO’s 75th Anniversary, there is progress to applaud; however, as UNSCR 1325 reached its 25th anniversary, there is also a reckoning to see how much progress can be measured and what tactics are needed to stay the course.

Table 1: NATO Members: WPS National Action Plans (NAPs), Gender Equality and WPS Indices Rankings

| Country | Year joined | First NAP | Most recent NAP | 2023 (EIGE) Gender equality index (100 = full equality) | 2023/24 WPS index rankings (0-1) | Ranking: WPS index (comparing 177 countries) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Albania | 2009 | 2018 | 2018-2020 | 0.796 | 45/177 | |

| 2 | Belgium | 1949 | 2008 | 2017-2021 | 76 | 0.902 | 11/177 |

| 3 | Bulgaria | 2004 | 2020 | 2020-2025 | 65.1 | 0.826 | 35/177 |

| 4 | Canada | 1949 | 2010 | 2023-2029 | 0.885 | 17/177 | |

| 5 | Croatia | 2009 | 2011 | 2016 | 60.7 | 0.862 | 25/177 |

| 6 | Czechia | 1999 | 2017 | 2017-2020 | 57.9 | 0.884 | 18/177 |

| 7 | Denmark | 1949 | 2005 | 2020-2024 | 77.8 | 0.932 | 1/177 |

| 8 | Estonia | 2004 | 2010 | 2020-2025 | 60.2 | 0.892 | 13/177 |

| 9 | Finland | 2023 | 2008 | 2023-2027 | 74.4 | 0.924 | 4/177 |

| 10 | France | 1949 | 2010 | 2021-2025 | 75.7 | 0.864 | 24/177 |

| 11 | Germany | 1955 | 2013 | 2021-2024 | 70.8 | 0.871 | 21/177 |

| 12 | Greece | 1952 | 2024 | 2023-2028 | 58 | 0.766 | 51/177 |

| 13 | Hungary | 1999 | 57.3 | 0.835 | 32/177 | ||

| 14 | Iceland | 1949 | 2008 | 2018-2022 | 0.924 | 4/177 | |

| 15 | Italy | 1949 | 2010 | 2020-2024 | 68.2 | 0.827 | 34/177 |

| 16 | Latvia | 2004 | 2020 | 2020-2025 | 61.5 | 0.872 | 20/177 |

| 17 | Lithuania | 2004 | 2011 | 2020-2024 | 64.1 | 0.886 | 16/177 |

| 18 | Luxembourg | 1949 | 2015 | 2018-2023 | 74.7 | 0.924 | 4/177 |

| 19 | Montenegro | 2017 | 2008 | 2019-2022 | 0.808 | 41/177 | |

| 20 | Netherlands | 1949 | 2008 | 2021-2025 | 77.9 | 0.908 | 9/177 |

| 21 | North Macedonia | 2020 | 2013 | 2013-2015 | 0.798 | 44/177 | |

| 22 | Norway | 149 | 2006 | 2023-2030 | 0.92 | 7/177 | |

| 23 | Poland | 1999 | 2018 | 2018-2021 | 61.9 | 0.859 | 27/177 |

| 24 | Portugal | 1949 | 2009 | 2019-2022 | 67.4 | 0.877 | 19/177 |

| 25 | Romania | 2004 | 2014 | 2014-2024 | 56.1 | 0.8 | 42/177 |

| 26 | Slovakia | 2004 | 2020 | 2021-2025 | 59.2 | 0.856 | 29/177 |

| 27 | Slovenia | 2004 | 2010 | 2018-2020 | 69.4 | 0.824 | 36/177 |

| 28 | Spain | 1982 | 2007 | 2017-2023 | 76.4 | 0.859 | 27/177 |

| 29 | Sweden | 2024 | 2006 | 2016-2020 | 82.2 | 0.926 | 3/177 |

| 30 | Türkiye | 1952 | 0.665 | 99/177 | |||

| 31 | United Kingdom | 1949 | 2006 | 2023 | 0.86 | 26/177 | |

| 32 | United States | 1949 | 2011 | 2023 | 0.823 | 37/177 | |

| Average | 67.52 | 0.86 | 25.66 |

Sources: NAP data gathered from Peacewomen.org and aligned with Oursecurefuture.org. The Gender Equality Index rankings are from European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) and the WPS Index Rankings from the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace, and Security.

Table 2: NATO Gender Distribution by Grade per Diversity and Inclusion Charts, 2018-2023

Sources: All data collected from the NATO Diversity and Inclusion reports 2019 through 2022. The 2023 format switched to a scorecard that was only for the January through March 2023 time frame, but the rest of 2023 has not yet been released. Note that the 2021 report removed U grade appointments and added L grades, which accounts for the huge change in numbers. See section on NATO Country Findings for additional context.

NATO Percentage of Women Senior Leaders per Diversity and Inclusion Reports, 2018-2023

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| International Staff (IS) | 25% | 27% | 30% | 32% | 38% | |

| International Military Staff (IMS) | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | |

| Other | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | |

| NATO HQ subtotal | 23% | 25% | 10% | |||

| Allied Command Operations (ACO) | 16% | 20% | 14% | 14% | 13% | |

| Allied Command Transformation (ACT) | 0% | 0% | 25% | 33% | 20% | |

| NATO Airborne Early Warning & Control Force | 0% | 0% | ||||

| NATO Defense College (NDC) | 0% | 0% | ||||

| Combined Air Operations Centre (CAOC) and Combat Air Command and Control Centre (CACCC) | 0% | 0% | ||||

| NATO Communications & Information Systems Group (NCISG) NATO Signal Battalion (NSB) and HQ | 0% | 0% | ||||

| Closing Entity | 0% | not included | ||||

| Strategic commands and other entities subtotal | 9% | 20% | ||||

| NATO Communications and Information Agency (NCIA) | 17% | 22% | 18% | 21% | 21% | |

| NATO Support and Procurement Agency (NSPA) | 90% | 13% | 29% | 16% | 16% | |

| NATO Eurofighter and Tornado Management Agency (NETMA) | 80% | 8% | ||||

| Science and Technology Organization (STO) | 29% | 14% | ||||

| NAEW & C Programme Management Agency (NAPMA) | 0% | 0% | ||||

| NATO Helicopter Design and Development Production and Logistics Management Agency (NAHEM) | 0% | not listed | ||||

| NATO Alliance Ground Surveillance Management Agency (NAGSMA) | 25% | not listed | ||||

| NATO Medium Extended Air Defense System Management Agency (NAMEADSMA) | 0% | not included | ||||

| Other | 14% | 10% | 9% | |||

| Agencies subtotal | 10% | 11% | ||||

| NATO-wide civilian total | 15% | 17% | 19% | 20% | 22% | 36% |

Note: The 2024 scorecard lists 14 entities to breakout women in senior leadership, but none track to any of previously used entities. They range from 67% to 0%. Subtotals were abandoned after 2020.

Check out all the great articles Small Wars Journal has to offer.

The post A La Carte Feminism: The Limits of NATO’s WPS Commitments in a Time of Crisis appeared first on Small Wars Journal by Arizona State University.

Related Articles

What’s pushing Canada and China closer?

Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney hails his visit to China as ‘historic’.

Israel objects to U.S. announcement on Gaza reconstruction committee

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s office said in a statement that the Gaza...

Syrian army takes control of Deir Hafer, Maskana under agreement

Syrian government troops have moved into dozens of towns and villages in...

1/17/26 National Security and Korean News and Commentary

Access National Security News HERE. Access Korean News HERE. National Security News:...

Leave a comment