- Home

- Advertise With us

- World News

- Tech

- Entertainment

- Travels & Tours

- Contact US

- About us

- Privacy Policy

Top Insights

10 Classic Albums That Influenced Nu Metal

The once-maligned genre of nu metal has since been re-evaluated as the important, influential, unique moment for music and culture that it always was, and it’s been everywhere lately, so we’ve been taking a look back through a fresh lens. We recently talked about 10 nu metal albums that even nu metal skeptics need to know, and now here’s a list of 10 classic albums that influenced nu metal. The purpose of the list is not just to shine a light on the bands that influenced an era-defining style of music–some of whom go a lot more overlooked today than others–but also to show how nu metal was actually a logical extension of a lot of bands who did tend to be taken more seriously than nu metal did in its prime. If you like the albums on this list and still haven’t given nu metal a chance, some of it might surprise you.

One of the most interesting things to me about looking at nu metal from this angle is seeing that nu metal was often more influenced by non-metal than by metal. A lot of the early nu metal grew out of the freakiest corners of the alternative rock world, and a good chunk of it also came from industrial and hardcore. If you ask me, the line between proto-nu metal and nu metal is Korn’s debut album, and if that album didn’t end up being credited with starting an entire genre, it would be easy to picture Korn grouped more with the bands on this list than with Limp Bizkit. Similarly, squint in a different direction and some of the bands on this list could’ve easily passed as nu metal. Depending on who you talk to, maybe some of them did.

Korn’s debut came out in 1994, but genres don’t develop overnight so this list spans from 1989 to 1996, including a handful of albums that came out after the most widely-accepted “first nu metal album” came out. As nu metal continued to evolve throughout the ’90s and into the 2000s, you can really hear the influence that some of the later albums on this list brought to the table.

Other things to note: I stuck to one album per band, and choosing just 10 albums means leaving off tons of other artists who influenced nu metal. Lastly, even if you don’t care about their impact on nu metal, these are just 10 incredible albums that any fan of rock music should know.

Read on for the list, in chronological order…

Faith No More – The Real Thing (1989; Slash/Reprise)

You’d be hard-pressed to find a nu metal band that doesn’t cite either of Mike Patton’s most famous bands–Faith No More and Mr. Bungle–as influences. Korn’s Jonathan Davis said Faith No More’s 1989 album The Real Thing “showed everybody you could do heavy music and not be ‘metal.’” The band’s funk-infused rhythms reverberated throughout the entire genre of nu metal, as did Mike Patton’s voice, a deeply strange wail that sometimes veered into sorta rapping. It’s easy to trace iconic nu metal singers like Chino Moreno and Serj Tankian back to Mike Patton, not to mention post-hardcore wailers like Glassjaw’s Daryl Palumbo and At the Drive-In’s Cedric Bixler-Zavala, both of whom also happened to work with nu metal producer Ross Robinson and could at least pass as nu metal-adjacent.

Faith No More’s own roots were more in post-punk than in heavy metal, and (after putting out two albums with lead singer Chuck Mosley) the band met Mike Patton when he was fronting a punky, thrashy iteration of Mr. Bungle, a few years before Bungle turned into the avant-garde rock band that they’re most famous for being. When they came together on 1989’s The Real Thing, they came off as an extension of the freakiest parts of the American alternative rock underground, two years before alternative rock had its big Nirvana-fueled explosion. The Real Thing is a melting pot of funk, post-punk, metal, hip hop, prog, and more, all fused together to the point that it was too weird to truly fit in anywhere. It’s too pop to have really fit in with the metal world, too strange to be pop (at least outside of the album’s breakthrough hit “Epic”), and too flamboyantly bright to have fit in with the then-nascent, angst-ridden grunge movement. For all of those reasons, it’s a proto-nu metal album that never sounds like nu metal, but you can see and hear why so many nu metal bands looked up to this record. Metal was already getting slower and groovier by the dawn of the 1990s; The Real Thing convinced a generation of headbangers that it needed to get weirder too.

Ministry – The Mind Is a Terrible Thing to Taste (1989; Sire)

Nu metal was just as influenced by funk metal as it was by industrial metal, and the line between nu and industrial metal is often so faint you can barely see it. Such is the case with industrial metal pioneers Ministry. Al Jourgensen started Ministry as a gothy synthpop project in 1981 and then embraced new wave (allegedly due to label pressure) before settling into the darker industrial vibe that’s clearly his true calling. But it wasn’t until falling back in love with guitars and inviting some thrash metal influence into Ministry’s 1988 album The Land of Rape and Honey that the most classic and influential version of Ministry was born. On its 1989 followup The Mind Is a Terrible Thing to Taste, the heaviness intensified. Jourgensen started jamming with guitarist Mike Scaccia of Texas thrash band Rigor Mortis, and the seeds of those early collaborations bore fruit on this album, even though Scaccia didn’t join Ministry until after the album was completed. On songs like album opener “Thieves” and “Breathe,” Bill Rieflin’s drumming was so manic that Ministry hired a second drummer when they toured behind it–paving the way for the likes of Slipknot and Mushroomhead in the process. “Test,” with lead vocals from rapper K-Lite, is a pioneering industrial rap metal song that set the stage for too many nu metal bands to count. There are some very ’80s production elements on The Mind Is a Terrible Thing to Taste, but from a pure intensity standpoint, this rivaled even the heaviest nu metal bands that would emerge a decade later.

Rollins Band – The End of Silence (1992; Imago)

It makes sense that the recent nu metal resurgence partially had to do with the genre’s influence on rising hardcore bands, because there’s a good argument to be made that nu metal can be traced even more directly to hardcore than it can to metal (and it’s an argument I’ll make a few more times in this article). After leading Black Flag on their heavier, later records that helped invent grunge and sludge metal, Henry Rollins launched his own Rollins Band, which saw him pushing into even heavier, chunkier territory. He was joined by the rhythm section of bassist Andrew Weiss and drummer Sim Cain, who both played in the hardcore-adjacent instrumental funk/jazz rock band Regressive Aid before backing Black Flag guitarist Greg Ginn in his own instrumental band Gone, and guitarist Chris Haskett, who Rollins knew from his days in the DC hardcore scene. By the time of their breakthrough third album The End of Silence (their last with Weiss), they’d come up with a fusion of funk, metal, and hardcore that set the stage for so much heavy music of the ’90s and left a clear impact on nu metal. Just as influential as the thunderous instrumentals was Rollins’ shouted delivery, which sounded tough on the surface but was steeped more in vulnerable emotion than aggression. I don’t know that Henry himself necessarily liked nu metal, but he did see something in it that a lot of his peers didn’t: “The payoff on those songs, when that big guitar comes in,” he once said, “you can’t help it, you’re like, hell yeah, let’s go wreck something!” Given the similar type of catharsis all throughout The End of Silence, it’s not hard to hear why he identified with it.

Helmet – Meantime (1992; Interscope)

Helmet grew out of NYC’s avant-garde/noise and hardcore scenes of the late ’80s and early ’90s, and they came out with a sound of their own that was informed by both and beholden to neither. They were heavy enough to be associated with metal, but they never really seemed like they set out to become a metal band and they often resisted being referred to as one. And it was their unique approach to heaviness that made them so influential on the nu metal boom that would ensue just a few years after they released their major label debut Meantime. Their downtuned guitars helped give them a thick low end that so many nu metal bands replicated, but what really earns Helmet a spot on this list are those choppy, chunky rhythms. On Meantime, Page Hamilton and Peter Mengede’s power chords are basically part of the rhythm section, and they come together with bassist Henry Bogdan and drummer John Stanier (later of Tomahawk with Mike Patton, Battles, and more) to create these sharp, syncopated rhythms that are built to have bodies flinging. It’s not funk metal or groove metal but these thick slabs of heavy, groove-based music had a similar effect, as well as a similar impact on nu metal. Limp Bizkit’s Wes Borland once told Stereogum that his band’s approach early on was “taking those Helmet slaughterhouse riffs and combining it with like Carcass riffs and treating it more like a hip-hop Ministry song,” and they’ve been cited as an influence by Deftones, Linkin Park, Slipknot, Papa Roach, and so many other nu metal bands. And it’s something that Page Hamilton himself has picked up on. “I hear it all over the place,” he said of Helmet’s influence in a 2010 interview. “Kids today have no idea at this point, because they got into, say, Korn, System Of A Down… I’ve heard Helmet riffs in Evanescence.”

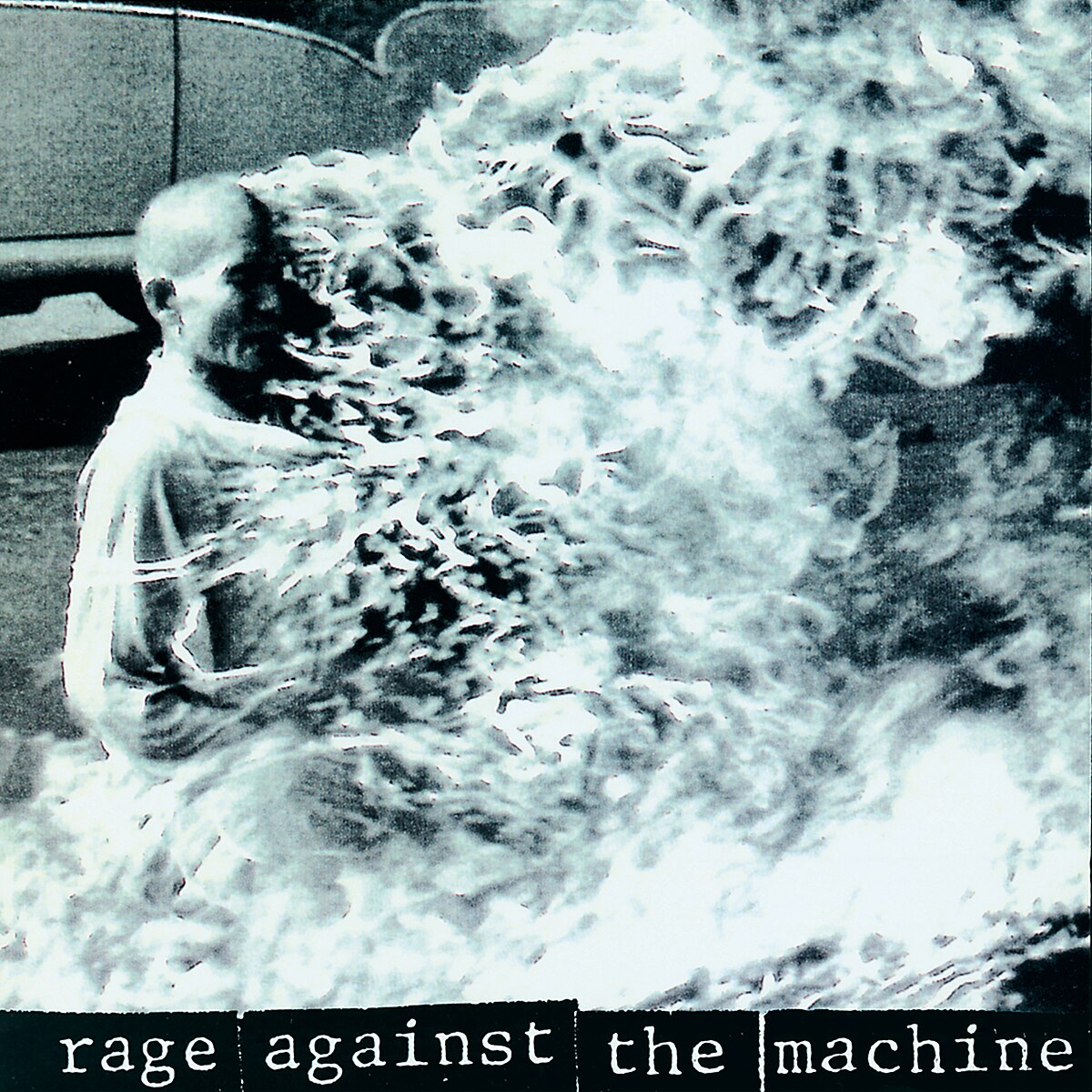

Rage Against the Machine – Rage Against the Machine (1992; Epic)

There were rap/rock fusions that existed before Rage Against the Machine’s 1992 self-titled debut album, but anytime you listen to one of the many nu metal songs with rapping, you’re listening to a style of music birthed by this LP. Even Scott Ian of Anthrax, whose 1987 Public Enemy collab “Bring the Noise” is arguably an earlier form of rap metal than RATM, once said, “It’s definitely Rage Against the Machine for me that created rap metal, nu metal, whatever you want to call it.” Guitarist Tom Morello had roots in funk metal, having previously played in the band Lock Up, while vocalist Zack de la Rocha previously fronted the Revelation Records-signed hardcore band Inside Out. (A top 10 example of nu metal’s roots being in hardcore.) It was after Inside Out’s breakup that Zack started adding hip hop cadences to his shouted bark and rapping at local clubs, and it was at one of those clubs that he caught Tom’s ear. When they formed Rage Against the Machine with Brad Wilk on drums and Zack’s childhood friend Tim Commerford on bass, Tom beefed up his guitar playing style and turned it into something that was both heavier and more experimental, while Zack turned his love of hip hop and hardcore into some of the most cutting vocal performances of the 1990s. Armed with uncompromisingly political lyrics that were in line with plenty of punk and rap but shocking in a mainstream context, Rage came out swinging with a damn-near-perfect debut LP that–without any exaggeration–changed the world. Produced by Garth Richardson (who went on to produce nu metal records for the likes of Mudvayne and Kittie), the record has a hard, clear shell that’s perfect for the attack within. From the body-slamming rhythms to Zack’s aggression on the mic, RATM’s debut influenced almost every major nu metal band, whether that band rapped or not.

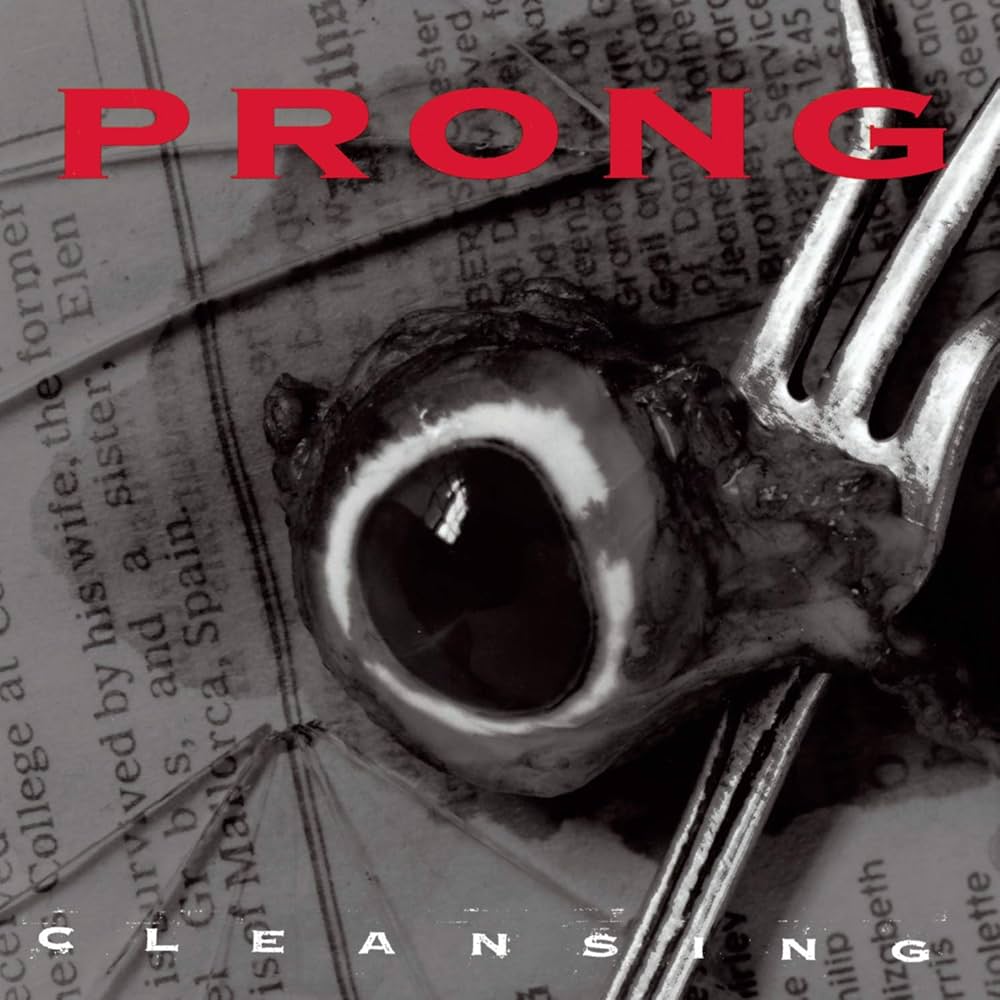

Prong – Cleansing (1994; Epic)

I’m not much of a gambler, but I’d be willing to bet that there are nu metal fans who have never listened to Prong and Prong fans that still insist on tuning out nu metal, and I’d urge both to change that. Cleansing was released 10 months before Korn’s debut album, and if it came out four or five years later, it probably would’ve gotten lumped right in with the nu metal boom. If you like nu metal, you like Cleansing, and vice versa. Prong emerged in 1986 as a crossover thrash band within the New York Hardcore scene, and by 1991’s Prove You Wrong, they started shaving off their thrash tendencies and moving more towards the sounds of groove metal and industrial metal. On 1994’s Cleansing, the transformation was complete. They had choppy, staccato riffs/rhythms that weren’t unlike their NYC neighbors Helmet, and they found themselves navigating similar waters to Pantera and Sepultura, both of whom they toured with in the Cleansing era. Then-new bassist Paul Raven and keyboardist John Bechtel had previously played together in Killing Joke (and industrial supergroup Murder Inc), and they brought a taste of British industrial that made for a perfect storm with bandleader Tommy Victor and drummer Ted Parsons’ NYHC punch. The album was produced by Terry Date, who had previously worked with Pantera and Soundgarden and who went on to become a key part of nu metal after working with Deftones, Limp Bizkit, and Staind, and it’s not hard to imagine nu metal bands hearing Cleansing and wanting that production style for themselves. Cleansing has the robotic precision of industrial and the bludgeoning attack of hardcore and metal without ever really sounding too much like one of those genres or the others. It found a refreshingly new–or should I say nu–middle ground that influenced an entire generation.

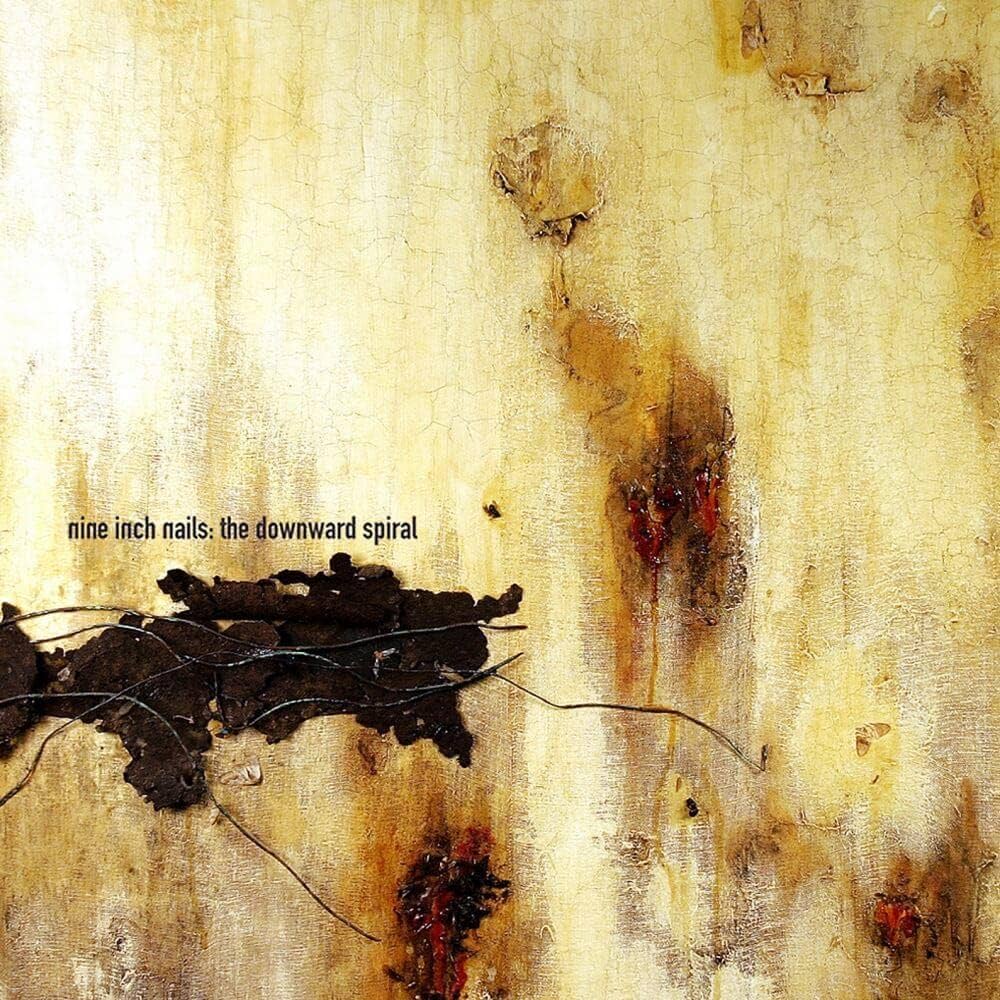

Nine Inch Nails – The Downward Spiral (1994; Nothing/Interscope)

The roots of nu metal could be heard in Nine Inch Nails’ music from the start. Even on the synth-driven industrial rock of their 1989 debut LP Pretty Hate Machine, the finger-pointing anger of breakthrough single “Head Like A Hole” set the tone for so many of the soon-to-form nu metal bands. On their heavier, more guitar-driven 1992 EP Broken, they came out with a more metallic sound that echoed all throughout the nu metal boom. But the album that really captured the full scope of Trent Reznor’s vision and altered the trajectory of alternative music forever was 1994’s The Downward Spiral. Its influence spans far and wide, not limited to nu metal by any means but one of the most major informants of that genre. The metaltronic assault of “Mr. Self Destruct” and “March of the Pigs” echoed all throughout nu metal’s heaviest bands. The snarled shout of “IF THERE IS A HELL / I’LL SEE YOU THERE” on “Heresy” was nu metal’s attitude in a nutshell. The album’s atmospheric, electronically-manipulated approach to heavy music was one of the most obvious precursors to early-aughts-era Deftones and Linkin Park. When nu metal did take over the world, Trent criticized it in interviews and significantly toned down his own metal elements on The Downward Spiral‘s long-awaited 1999 followup The Fragile. But for those who did want more where The Downward Spiral came from, nu metal became a place where you could be sure you’d find it.

Orange 9mm – Driver Not Included (1995; EastWest)

Orange 9mm were, in many ways, the East Coast counterparts to Rage Against the Machine. Like Zack de la Rocha, Orange 9mm vocalist Chaka Malik fronted a Revelation Records-signed hardcore band who released one EP in 1990 before breaking up, Burn. After that, Chaka too began embracing hip hop cadences, and he teamed up with a riff-master of his own: Chris Traynor, formerly of the New York post-hardcore band Fountainhead (and later of the aforementioned Helmet). Orange 9mm’s self-titled 1994 debut EP came out on Revelation and they remained directly tied to the NYHC scene, not just tangentially connected to it, as they put out a major label debut album that left an undeniable mark on the developing nu metal genre. That album, Driver Not Included, is timeless and its influence can be heard everywhere. The riffs and rhythms really slam and give you that same full-body catharsis that the Limp Bizkits of the world helped bring to the masses, and Chaka’s shout-rapped delivery paved the way for so many of the singers that were blaring out of KROQ by the end of the ’90s. Orange 9mm crossed paths with nu metal early on–they opened Deftones’ Adrenaline tour and shared stages with Korn when NYHC veterans Sick Of It All took both bands on tour in 1995–but Orange 9mm disappeared from the mainstream by the time of their poor-selling 1999 album Pretend I’m Human and broke up soon after. They never got to capitalize on the success of the genre they helped invent, and it’s a shame. All these years later, Driver Not Included still sounds like something that would’ve conquered the world if it came out during nu metal’s peak.

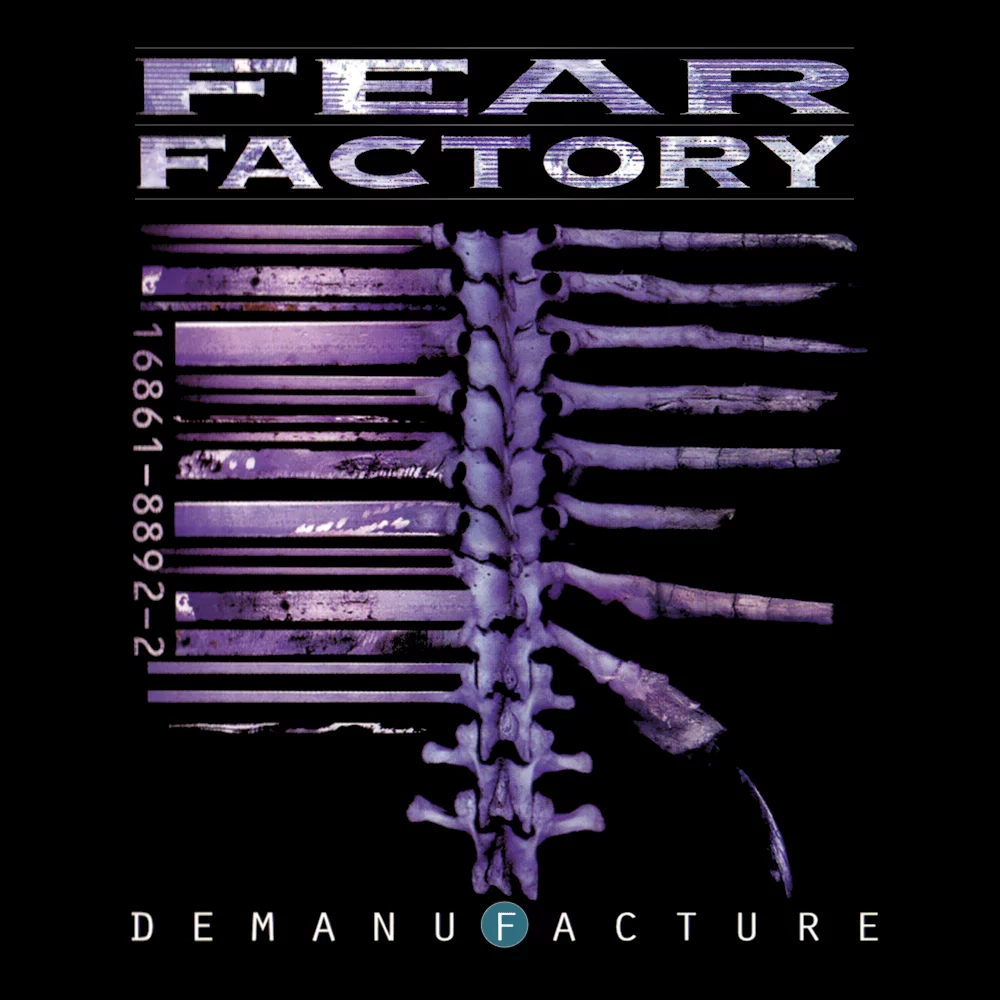

Fear Factory – Demanufacture (1995; Roadrunner)

Fear Factory actually got their start as a death metal band, as heard on their archival demo album Concrete (the first album ever produced by Ross Robinson, who went on to produce Korn’s first album and become one of nu metal’s most in-demand producers) and their 1992 debut LP Soul of a New Machine, but it was after diving head-first into industrial metal that they came out with the classic Fear Factory sound (and solidified the classic Fear Factory lineup) on 1995’s Demanufacture. Synthesizers and sampling were present, but guitarist/bassist Dino Cazares, drummer Raymond Herrera, and bassist Christian Olde Wolbers also knew how to churn out a pulsating, robotic attack with just their live instruments. On this LP, vocalist Burton C. Bell really came into his own, with a combination of throat-shredding roars and clean-sung melodies that was far more accessible than Fear Factory’s early work and in some ways even more aggressive. From the caveman stomps to the tuneful hooks, Demanufacture gave countless nu metal bands a formula to use, and as that genre popped off, Fear Factory embraced it. They toured and collaborated with nu metal bands and their 2001 album Digimortal was seen by many as FF’s own foray into the nu. Whether or not Fear Factory ever truly became nu metal is still up for debate, but regardless, Demanufacture remains the blueprint for so much of it.

Tool – Ænima (1996; Zoo/Volcano)

Tool and Maynard James Keenan’s other band A Perfect Circle often ran in the same circles as nu metal bands and had a lot of the same fans, but Tool themselves were always more of a progressive/psychedelic band at heart. Still, it’s easy to hear why the nu metal community embraced them, and the entire genre would’ve sounded a lot different without their influence. They came up alongside a lot of the other bands on this list (Maynard sings on Rage Against the Machine’s first album, Henry Rollins appears on Tool’s first album), and Tool’s early releases like 1992’s Opiate EP and 1993’s Undertow left a clear impact on the first generation of nu metal bands. But the album I’d like to focus on is their 1996 sophomore album Ænima, which came out during nu metal’s early years and permanently altered the trajectory of that genre and a handful of others. It’s the first album with the classic lineup of Maynard, guitarist Adam Jones, drummer Danny Carey, and bassist Justin Chancellor, the last of whom made his Tool debut on this album, and Chancellor’s basslines took Tool’s music to a new dimension–he and Adam Jones mostly eschewed the typical guitarist/bassist dynamic in favor of combining as one 10-string beast. When they did go for headbanging, body-slamming stuff, as they did on songs like “Stinkfist,” “Ænema,” and “Pushit,” they brought a weirdo flare to it that informed several of nu metal’s biggest oddballs. When nu metal singers wanted to go somewhere softer and more melodic, they so often borrowed from Maynard, and look no further than the sheer amount of ‘fuck you’s on “Ænema” to see that they borrowed from him at their angriest too. There’s also a lot about this 77-minute album that doesn’t sound anything like nu metal, or like anything else for that matter. It was imitated but never replicated or surpassed.

**

—

SEE ALSO:

* 10 Nu Metal Albums That Even Nu Metal Skeptics Need To Know

Related Articles

Kevin Smith’s Bizarre A24 Horror Movie On Netflix Has To Be Seen To Be Believed

Kevin Smith once directed a truly bizarre body horror flick for A24....

Landman Star Jacob Lofland Played A Small But Important Role In Joker 2

Landman star Jacob Lofland doesn’t have a whole lot of screen time...

Young and the Restless Next Week: Jack Rages at Billy’s Betrayal! – Explosive Abbott Brothers War Ignites!

Young and the Restless spoilers for next week indicate Jack Abbott (Peter...

Bold and the Beautiful: Eric’s New Move is Slap in Ridge’s Face!! – Brutal Power Play Rocks Forrester Family!

Bold and the Beautiful gives Eric Forrester (John McCook) super excited to...

Leave a comment